The Importance of Dialogue in Your Script

Whether you’re writing a feature film screenplay or a television pilot, many beginner writers don’t place enough importance on dialogue.

Some writers believe that if they have a good concept, that will be enough to land them a script sale and break them into the business. Thinking this way is a missed opportunity, and will limit your chances of success.

A spec script is a showcase for your writing and, in many cases, it will be your introduction to industry professionals. Good dialogue can help give your script an extra edge or X factor that distinguishes your screenplay in the film and television marketplace.

Dialogue is also arguably where a writer gets to shine most.

Dialogue adds a human touch to a story, and it’s often akin to lyrics in a song. In the same way that many people will sing along to their favorite tune, audiences are always quoting lines from their favorite movie or TV show. How many times have you heard someone quote a line from Pulp Fiction or Breaking Bad?

Dialogue is what usually sticks with audiences after watching a movie or TV show, and it’s not any different when an industry professional reads your screenplay or TV pilot. Many A-list screenwriters made a name for themselves due to the strength of their dialogue, writers such as Paul Schrader, Aaron Sorkin, Quentin Tarantino and Diablo Cody.

So, how do you write good dialogue?

It all begins with your voice.

Finding Your Voice

When writing a screenplay, don’t underestimate your voice as a writer. Your voice is the very unique way you look at the world, and how you express yourself. It’s different from anyone else’s voice, and particular only to you.

Think of the screenwriters who have made a name for themselves. Diablo Cody has a voice: that’s why Juno sold and got her an Oscar®. Quentin Tarantino has a voice. Damien Chazelle has a voice. Mike White has a voice. Whether you like these writers or not, there’s no denying they have a distinct style and worldview that informs their characters and storytelling.

And their voice as writers is largely expressed via their dialogue.

Inserting Your Voice Through Dialogue

One of the easiest ways to convey your voice is through dialogue. Dialogue is the voice of your characters, but can also showcase your voice as a writer.

Are you a naturally funny person? When you’re hanging out with family or friends, do you make people laugh? Do you have a witty repartee with coworkers? If so, you could try inserting that humor into your dialogue.

Even if you’re not writing a comedy, exhibiting a flair for witty banter and one-liners can lead to unexpected opportunities. These days many action, horror and thriller films contain humorous dialogue. If you can work in a memorable quip for the hero during an action set piece, you’ll be a writer in high demand.

Generally speaking, the more you can do as a writer, the more professional opportunities you’ll have. From Carl Gottlieb (The Jerk, Jaws) to Danny McBride (Eastbound and Down, Halloween), many comedic writers have had long and successful careers by demonstrating tonal adaptability, and inserting their personality and wit into thriller/horrors.

But what if you’re not a naturally funny person?

Obviously not all films are humorous, so it’s not essential to be funny, but you can still express your personality via your dialogue. Maybe you have a poetic or philosophical nature. Think of Christopher Nolan (The Dark Knight, Oppenheimer) and Martin McDonagh (In Bruges, The Banshees of Inisherin); even though they’re very different writer-directors working within different genres, what their films share is an infusion of their personal obsessions and philosophical musings into their dialogue.

In Nolan’s case, he was even able to work these preoccupations into a tentpole franchise. During two scenes of The Dark Knight (written by Nolan and his brother Jonathan), the Joker expresses his anarchistic ethos and worldview to Batman and Harvey Dent. One of the pervading themes of Nolan’s work is humankind trying to control the chaos of existence: this idea is frequently debated between his characters. The Joker represents the antithesis of Batman’s quest for control, and likewise offers a challenge to Nolan’s own personal fixations.

Before becoming an acclaimed director, Oliver Stone was an Oscar-winning screenwriter known for projects as varied as Midnight Express, Conan the Barbarian and Scarface. However, all of these scripts — even Conan the Barbarian — had a political undercurrent, and they all focused on power struggles.

Stone’s calling card spec script that broke him into the industry was Platoon, which detailed his personal experience as a soldier in Vietnam, but it also contained the above preoccupations. Stone’s characters are often expressing their machismo and distrust of “the system,” which they view as corrupt. This is perhaps most evident in the character Tony Montana’s dialogue in Scarface, in which he expresses his disdain for a hypocritical elite and justifies his tough and streetwise moral code.

But what if you didn’t fight in a war, or don’t have any profound or special interests? What if you’re just an average person and you don’t think you’re particularly interesting?

Chances are you’re more interesting than you realize, and you should view writing dialogue as an opportunity to dive deeper into yourself and discover who you truly are as a person. When you discover what’s unique about you, there’s a good chance you’ll likewise discover your voice as a writer.

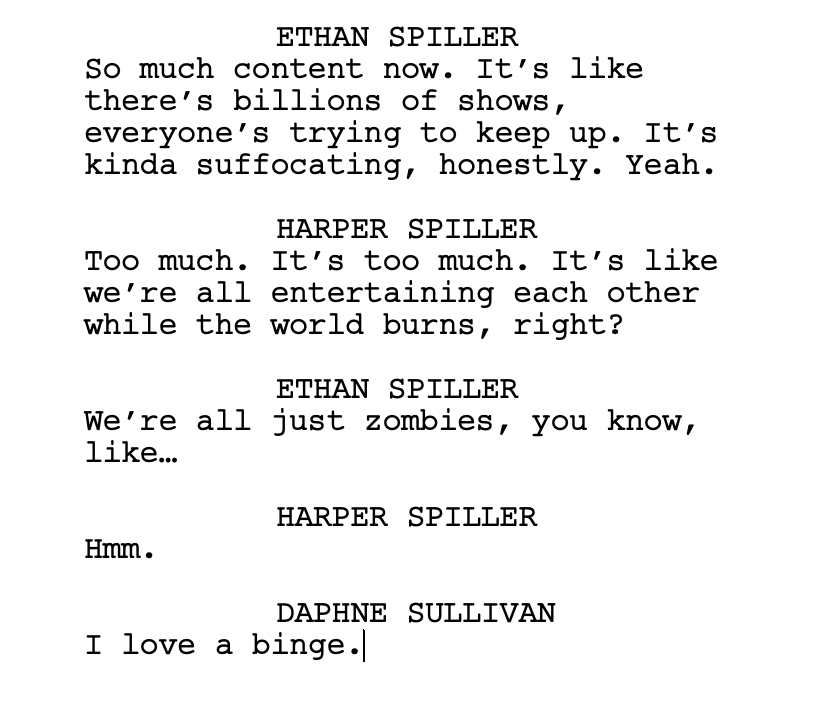

Maybe you’re an anxious person or — let’s be completely honest here — you’ve been described as “neurotic.” You might view this as negative, but many A-list screenwriters have expressed their anxiety via their characters’ dialogue: Charlie Kaufman (Adaptation, Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind) made an entire career out of it. The White Lotus creator Mike White likewise expresses various anxieties and existential plight via his characters’ dialogue (oftentimes leading to a tense exchange or debate as seen below).

Your characters should be expressing things about yourself and the people around you: the good, the bad and the not so good. Not only is it gratifying to express yourself through writing, it will give your dialogue an authentic quality. Even if the scenarios you’ve created for your characters are far-fetched or otherworldly, if they talk like real people it will help make the reader believe whatever you throw their way (something a writer like Stephen King has always excelled at). This is what is referred to as “suspension of disbelief.”

This doesn’t mean turning your script into one big rant or therapy session, but inserting a little real-world anxiety can go a long way. Most people, no matter how perfect their lives might appear, have problems. The more awareness you have of these problems – as well as your own issues – the easier it’ll be for you to grapple with them in your dialogue, and more likely that your story will resonate with readers. The entertainment industry is filled with anxious and obsessive people; a few kindred spirits might just be reading and connecting.

So when writing dialogue, don’t forget to express yourself, and let your voice shine through.

Basic Tips For Improving Your Dialogue

Even if you’ve discovered your voice and you’re expressing it through your dialogue, the end result might still read as clunky or stilted (especially if you’re a beginner screenwriter).

Below are some basic tips for improving your dialogue:

Show Don’t Tell

Perhaps you’ve heard this one before? It’s quite possibly the most uttered advice in screenwriting. What Show Don’t Tell means is don’t have a character telling us something that’d be more cinematic and compelling to watch unfold visually. Film and television are visual mediums after all. Back in the day, before various filmmaking advancements, many movies were based on plays and, as a result, sometimes a more exciting plot development would have to happen off-screen and be described via dialogue. However, for at least half a century now, pretty much anything that can be imagined can be shot, so there’s no excuse for telling when you can be showing.

Avoid “On the Nose” Dialogue

This is likely the critique you’ll hear the most if you start getting feedback on your dialogue: that a line is too “on the nose.” This means the character is stating exactly what’s on their mind without any nuance or subtext. This doesn’t mean certain characters can’t speak directly about a situation or personal crises they’re dealing with, especially if it feels right for their character. Obviously in real life, some people speak more directly than others. The important thing is to make it sound like how a direct person actually speaks (with all their individualistic color and cadence).

Don’t Make All Your Characters Sound The Same

This is the one of the most consistent flaws in a beginner screenwriter’s dialogue: all the characters sound alike. In some cases, this might be due to the writer going too far with inserting their voice and, as result, they’ve turned every character into a surrogate for themselves. Even though a writer should have a voice and express themselves via their characters and their dialogue, the characters should still be characters. In addition to self-awareness, a writer should be aware of the various types of people they come across in life, and take note of the different ways they speak, behave, react to things, etc. Think of every character as a unique entity with their own worldview when writing their dialogue.

Don’t Make All Your Characters Curse

One thing that makes characters all sound alike is making them all curse throughout your script. Although the biggest culprits are beginner comedy writers, this can happen across the board. One of the main reasons for this – especially in a comedy script – is that cursing is an easy way to inject some humor or “edge” into your writing. Curse words are always on the tip of our tongues and ready to spew forth if we’re frustrated or have struck our knee against our desk. However, not everyone curses as freely as others, and this truth should be reflected in your dialogue.

Arguments Are Better Than Lovefests

Film and television thrives on conflict – it’s the narrative engine for nearly all storytelling – so if your characters are all getting along and never arguing, your script will lack drama and tension. Arguments also help to illustrate the differences in characters and their worldviews in an organic, naturalistic way.

Don’t Repeat What We Already Know

If we watched something play out in action or it’s already been discussed by characters, don’t repeat it in dialogue. If the reader of your script already knows something, it’s going to be boring for them to read all about it again. If it’s necessary to the story for a character to repeat something to another character, find a fresh way to do it, or perform the old editing trick of having the character begin telling us what we already know, but then transition to ‘moments later’ or a later scene.

Keep Exposition Down To A Minimum

Another critique you might get when industry professionals read your script is that there’s too much “exposition” in your dialogue. Exposition is a little more complicated than the above dialogue basics – and many times it’s unavoidable when telling a story.

How To Handle Exposition in Your Dialogue

One of the trickiest and biggest challenges for a screenwriter is how to best handle exposition.

What is exposition exactly?

It’s the insertion of expository information into a narrative. This info can be about the characters’ past or current situation, prior plot events, the setting or cultural backdrop.

If done effectively, exposition can add depth to your characters and strengthen your worldbuilding. After finishing a rough draft, however, a beginner writer might find their exposition is clunky and doesn’t read or flow naturally.

Below are five tips for handling exposition in your screenplay.

Avoid Info Dumps

Beginner screenwriters will often insert exposition bluntly and without much subtlety. In screenwriting development circles, these sections of the script are referred to as “information dumps” or more commonly “info dumps.” In the earlier days of cinema, movies would often employ voice-over narration to dump a bunch of information onto the audience; this technique is not favored today and is considered old-fashioned or possibly heavy-handed (when voice-over is utilized in a contemporary film, it’s usually for tonal or expressionistic purposes). Other formerly popular methods to avoid are having a character convey their entire backstory to a therapist or journalist, in a news report, or even through title cards. Of course there are always exceptions (e.g. if you’re going for a retro aesthetic), but generally speaking, if a sequence or dialogue exchange’s only purpose is to impart information, it’ll likely be viewed as an info dump and should be revised.

Don’t Front-Load Info

Not only do some beginner writers insert exposition too bluntly, many times they insert it too early. This results in another term used in development circles as “front-loading information.” In most cases, it’s better to space out exposition throughout your script. This technique is referred to as “indirect exposition”. In other words, you’re gradually cluing people in on the things they need to know about your characters and world, and not all at once. Think of it like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle slowly but surely forming a picture.

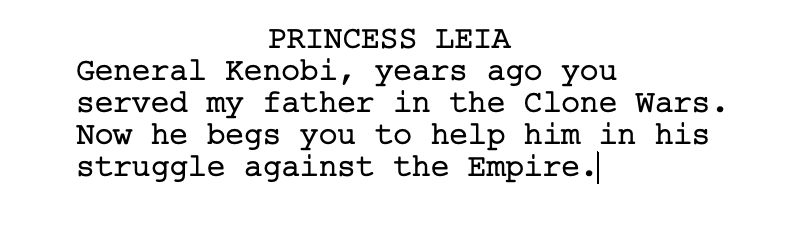

Interestingly enough, the film most associated with a front-loaded info dump is Star Wars via its iconic opening crawl, but if you actually dissect how information is imparted throughout the film, you’ll discover the crawl doesn’t actually reveal much. The crawl tells you that there’s a Galactic Empire and a Rebellion and some stolen plans for an ultimate weapon called the Death Star. What it doesn’t tell you, however, is anything about the main characters. It doesn’t tell you about the Jedi Knights and how Vader was Kenobi’s pupil who had “betrayed and murdered” Luke’s father. It doesn’t tell you that Kenobi once served Princess Leia’s father during the Clone Wars. It doesn’t tell you about how there’s this smuggler guy named Han Solo who owes money to Jabba the Hutt. The backstory of the main characters is conveyed gradually throughout the film: a line of dialogue here, a hologram there.

Keep It Conversational

One of the most organic and efficient ways to insert exposition is via a dialogue exchange. This is because in real life that’s how we usually discover things about people and situations. However, it’s best if dialogue isn’t used for a large and unnatural info dump. Short of being on a job interview or maybe a first date, people seldom reveal big chunks of their life story in conversation.

This is where it’s important to listen to how people speak in your day-to-day interactions; the more naturalistic you can make your dialogue, the less noticeable and artificial your exposition will seem. Think about how you gradually learn more about a coworker the longer you work with them, or you learn the truth about a romantic partner well after the first date.

A classic movie that’s a textbook example of naturalistic and indirect exposition is Jaws. Written by Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb (and a slew of uncredited writers), exposition is imparted constantly throughout the film, but it never sounds like exposition. Martin Brody’s backstory is first alluded to in a playful exchange between him and his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary), involving Martin’s butchery of a New England accent.

In a later casual exchange Ellen has with some locals at the beach, it’s revealed that the Brody family aren’t islanders. At the midpoint, Martin (Roy Scheider) opens up to Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) while they’re looking for the shark and reveals more about himself. Hooper’s backstory also comes out gradually and casually throughout the film: an anecdote here; a quip there.

And then there’s the USS Indianapolis speech — arguably the most celebrated monologue in cinema history — in which after some inebriated male bonding, we find out the back story of Quint (Robert Shaw) and why he’s got serious beef with sharks. No one ever thinks of this speech as exposition, but guess what: that’s exactly what it is. The main function of this speech is to impart information about Quint’s past, but it never feels that way. This isn’t simply because of how emotionally powerful the speech is, but also because of how organically it’s introduced.

Imagine if Quint launched right into the speech when Brody and Hooper first met up with him before their voyage: it would feel forced. But after these three men have been through the ringer with the Great White, and are getting drunk and telling stories about scars and broken hearts, it feels like the right time. The more conversational exposition is when it’s introduced, the better it will be received.

From there, Quint recounts his horrific experience as a survivor of the USS Indianapolis in his now legendary speech. Note how Quint’s tale needed to be coerced out of him, and how it naturally emerged from their drunken bonding and talk of scars and tattoos. The Indianapolis speech and its lead-in is the gold standard of how to use exposition in a script: the dialogue is naturalistic, revelatory, emotionally engaging and a highlight of this classic film.

Make It Entertaining

In the same way that Quint’s speech continues to captivate and move audiences today, the best exposition adds more to a screenplay than simply imparting information. As with other storytelling devices, exposition should be viewed as an opportunity for creativity and adding entertainment factor.

Perhaps the master of this is Quentin Tarantino. With his earlier films, a lot was made of Tarantino’s digressive and pop culture laden dialogue in which characters talk about everything from Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” to what a Quarter Pounder is called in Paris. But these conversations aren’t as trivial as they appear to be on the surface; more often than not, they convey things about the characters and, in many cases, foreshadow their fate.

Let’s examine the “Royale with Cheese” and “foot massage” exchanges between the characters Vincent (John Travolta) and Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) in Pulp Fiction. The most famous lines have little to do with the plot, but several important pieces of information are slyly worked into the exchanges. As the hitmen talk casually in the car and outside their target’s apartment, we learn the following: Vincent just got back in town after being abroad, there’s a familiarity between the two men indicating they’ve worked together before, their boss is an intimidating man named Marsellus Wallace who had a man thrown out of a window for massaging his wife’s feet, and most importantly, Vincent has to take Mrs. Wallace out on “a date.”

This sets up the entire “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife” chapter of the film — giving you all of the necessary information regarding the stakes of what’s to come — and yet it doesn’t feel like an info dump. It just sounds like a natural part of Vincent and Jules’ conversation because of how it was written, and because it follows their more trivial dialogue.

Imagine if there wasn’t the Royale with Cheese exchange beforehand, and they immediately started talking about Marsellus Wallace. The information would feel forced upon us, and we’d lose some of the film’s most fun and iconic lines.

When you’re wondering how and where to insert exposition into your narrative, ask yourself the following questions: What is the most interesting and inventive way to convey the information? Which characters should be conveying it? How can the information be imparted in a way that’s moving or entertaining?

Don’t Explain Too Much

In general, audiences respond to mystery and intrigue more than info dumps. In addition to gradually introducing your exposition throughout your script and making it more naturalistic and entertaining, sometimes consider if you even need it. If you’re not sure, there’s a good chance you don’t. Readers will often fill in the blanks if they’re engaged by a script and emotionally invested in the characters and story.

How To Write Naturalistic Dialogue

Another issue for beginner writers can be writing naturalistic dialogue. While your script might have good ideas or memorable sequences, if your dialogue reads as perfunctory or stilted and not how people actually talk, it can distance your reader from the story.

But how does a writer make their dialogue more naturalistic?

Listen to the people in your life. How do they speak in certain situations? How do they express themselves when they’re happy or when they’re angry? Also listen to people when you’re out in public. Whether it’s a social outing or running an errand, take in the fragments of conversations around you. Take note of how people speak to each other. When you’re a writer, no conversation should be ignored, even if it’s just for a fleeting moment. Think of your brain as a database, and always be collecting data for later use. You’ll start to pick up on common traits of how people speak to each other, and you’ll be able to discern naturalistic from stilted dialogue.

In real life, people don’t speak in perfectly rendered and well-orchestrated soliloquies. The way we talk to each other can vary depending on whom we’re speaking to: if we speak to an employer or authority figure, we’ll be more restrained and selective with our words. If we speak with a friend or family member, we’ll be looser and less selective. Real-life conversations are also sometimes messy and awkward. How many times have you said the wrong thing at the wrong time? How many times did you regret not saying the right thing? Some people even stammer or trip over their words. Our emotions can take over as well, pushing us to become boorish or even vulgar. We’ll talk over each other; shout over each other; etc.

Obviously this doesn’t make for good communication, but it’s an honest human flaw. We don’t have screenwriters constructing and penning our words. From Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network) to showrunner Jesse Armstrong and his talented writing staff on Succession, the rhythm and intricacies of human language is often at the forefront of acclaimed dialogue. A writer doesn’t acquire this skill from simply watching movies and TV; they listen to people and observe how they speak. They know how people will subtly make a suggestion, or evade a pointed question.

In the series Succession, characters shift from profanity laden insults to coyness depending on the latest curveball or power play. The character of “Cousin Greg” (Nicholson Braun) is a prime example of someone who speaks indirectly as a means of protection.

We’re not always direct with people. We dance around harsh or uncomfortable truths. When you talk to someone, do you often telegraph your feelings or your life’s trajectory? Think of the times in which you harbored resentment towards someone, but you didn’t want to address it directly in fear of some potential fallout. Or perhaps you’ve dealt with a passive-aggressive partner, family member or coworker? Many times in life, people mask their feelings, but picking up on subtext gives you a clue to what’s really going on. If you reflect this in character exchanges in your script, you’ll not only be writing naturalistic dialogue, you’ll be adding more tension and greater intrigue.

Of course, not all people are subtle and indirect when they speak. Screenwriters like Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver) and Nicholas Pileggi (Goodfellas) deal largely with working class or underworld characters who rarely mince words. They often say exactly what’s on their mind, but in a fiery and passionate manner, so it never feels too expository. It also feels true to the characters, such as in this exchange between Tommy (Joe Pesci) and Henry (Ray Liotta) in Goodfellas.

Naturalistic dialogue can mean the difference between a solid screenplay and an exceptional one. For example, screenwriter Dan O’Bannon’s original draft for Alien (1979) did a great job of establishing the futuristic world, some of the film’s most memorable set pieces and the overall mythos, but the Nostromo crew spoke without much distinction and came across as stock Sci-Fi characters. After Walter Hill’s rewrite of the script, the Nostromo crew spoke with far more distinction, and a working class earthiness that made them more relatable. Because of this, Alien ended up being more grounded than a typical Sci-Fi film, and all these years later it’s still a movie audiences emotionally invest in. We care about the Nostromo crew as they’re stalked by the Xenomorph because they seem like real people, and they seem like real people because they talk like real people.

So the next time you write a line of dialogue, ask yourself:

Does it sound like how this person would really talk?

Technical Tips For Writing Dialogue

In the past, screenwriters had to be mindful of typesets and alignments as they wrote dialogue in their scripts. Now there are screenwriting programs like Final Draft that automatically format your script to entertainment industry standards, so you can focus on what you do best – writing.

Whether it’s for a comedic effect or to insert some naturalism into your script, there might be times you want characters to speak simultaneously or talk over each other. Final Draft has the Dual Dialogue feature which enables paragraphs of dialogue to be easily formatted side by side.

Final Draft also has an Alternate Dialogue feature, which allows you to store alternate lines of dialogue in your screenplay file. This is great for collaborations, rewrites, or if you want to test different jokes in a comedic script.

Alternate dialogue is also useful if you’re not sure about a certain line. You can test out the different lines of dialogue by reading them out loud. Does one line flow better than the others? Is one line punchier? In general, reading your dialogue out loud is a good technique when you’re in doubt about certain lines. Does the dialogue sound natural? Does it roll off the tongue?

Finally, after you’ve finished a rough draft of your script, you should do a thorough “dialogue pass.” Read all the dialogue with a critical eye and be mindful of the characters speaking the lines. Does it sound like something that particular character would say? Is it phrased how they’d phrase it? Again, one of the biggest mistakes beginner writers make is having all their characters sound alike. Make sure the dialogue fits each individual character.

Like every skill, the more you do something, the better you get. Writing good or even average dialogue might initially seem daunting to a beginner writer, but over time you’ll improve and writing dialogue might even become your favorite part of the writing process. It’s where a writer truly gets to express themselves, giving their characters a voice that perhaps mirrors their own and the people around them. So the next time you think about what your character says and how they say it, take your time and have fun with it.

They’re not just the characters’ words.

They’re yours.

About The Author

Edwin Cannistraci is a professional screenwriter. His spec scripts PIERRE PIERRE and O’GUNN both sold with more than one A-list actor and director attached. In addition, he’s successfully pitched feature scripts, TV pilots and has landed various assignment jobs for Universal, Warner Bros, Paramount and Disney.

To read his articles on the craft of screenwriting visit the Final Draft Screenwriting Blog.