What Is a Story Beat in Screenwriting?

A story beat is a smaller event that happens within a larger sequence or narrative. Think of beats as the molecules of a screenplay or television script. Essentially, any moment that moves a story forward can be considered a beat, whether it's a minor or major event.

For example, in the original Star Wars, there are several events that keep moving the story forward:

- C-3PO and R2-D2 are introduced as the Empire attacks the Rebels and board their ship.

- Princess Leia hides the Death Star plans in R2-D2.

- C-3PO and R2-D2 escape with the Death Star plans.

- After landing on Tatooine, C-3PO and R2-D2 are captured by Jawas.

- Luke Skywalker is introduced as the Jawas sell C-3PO and R2-D2 to his Uncle Owen.

- R2-D2 plays Luke a holographic message from Princess Leia.

- R2-D2 flees the Lars homestead to deliver the plans and Leia’s message to Obi-Wan Kenobi.

- Luke and C-3PO go looking for R2-D2.

And so on.

Notice how each beat seamlessly sets up the next beat? Every story event — no matter how small or how big —is pushing the characters and narrative ahead. When placed together, beats make up your story and everything should come together like pieces of a puzzle.

What Is a Screenwriting Beat Sheet?

In screenwriting and film development, a beat sheet is a document that outlines the story beats for a script you either plan to write or have pitched to a production company and are now in the early stages of developing. In most cases, a writer will focus on the major beats, but sometimes a more detailed beat sheet will also include minor beats. It depends on how much you want to have worked out before going to script or how much a production company asks for. In most cases, a beginner screenwriter won’t be working with producers, so it’ll ultimately be your choice.

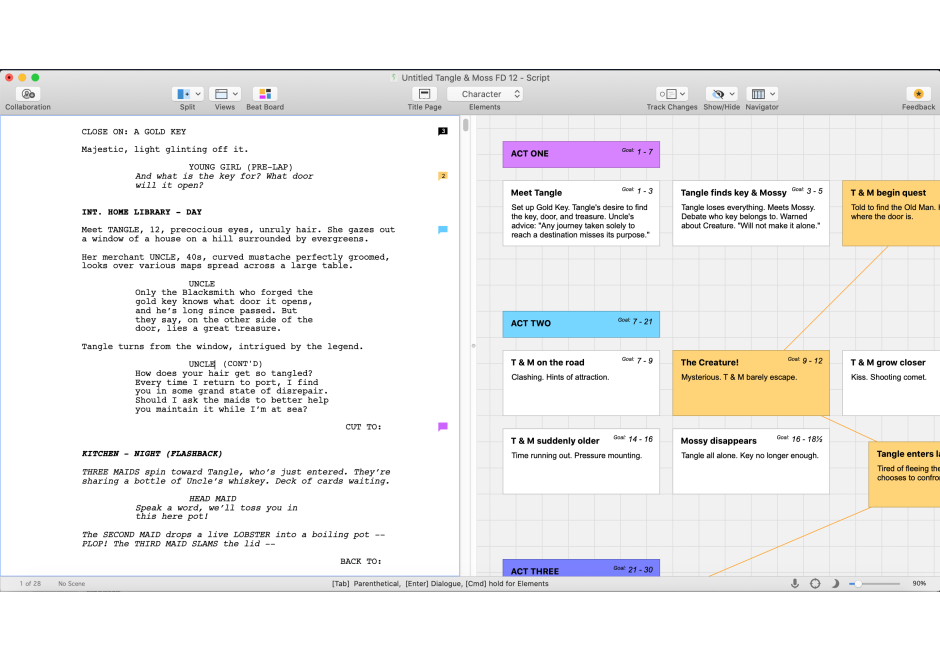

A variation of a beat sheet is a beat board, which is a preference of writers who respond better to ideas when they’re presented visually. In this scenario, a writer will jot down story beats onto an index card or sticky post and then place them onto a board of some sort or even directly onto their wall. This makes for easy and quick reference when writing your script and you can also move around the different beats and add or take away certain beats if you rethink certain aspects of your story. Final Draft also features a virtual Beat Board that easily integrates with your outline and screenplay.

How To Write a Beat Sheet

If you decide to go the document route, you might be wondering if there is any standard beat sheet format. There really isn’t and it comes down to what works best for you. However, if you need some beat sheet examples, here are three storytelling structures to follow. The first two examples are the basic frameworks that should contain your beats and the third example is a beat sheet template:

Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

Popularized by scholar and writer Joseph Campbell, the Hero’s Journey is a story structure that’s been used in many fantasy and adventure films (Star Wars being the most noteworthy). Arguably the basis for cinema’s three-act structure, the Hero’s Journey includes three main stages: the hero leaving his ordinary world to embark on an exciting but dangerous adventure; the hero facing several challenges in the new world(s) he has traveled to; and a resolution in which the hero faces his ultimate challenge and is forever changed.

Syd Field’s Three-Act Structure

In his 1979 book Screenplay: the Foundations of Screenwriting, author Syd Field expanded upon Campbell’s Hero’s Journey and created a more concise and specific three-act structure:

Act 1: The Setup

The story’s introduction where the setting, characters, and main conflict are established. This is also where the inciting incident occurs, forcing the protagonist onto a new path and setting up the next act.

Act 2: The Confrontation

A series of deepening conflicts and complications that build tension and suspense. This should be the largest act of your script and include the Midpoint, which is a major event that leads to no turning back for the protagonist. The conflict needs to be resolved at all costs and it typically leads to another major event or setback at the end of the act, commonly referred to as the lowest point.

Act 3: The Resolution

What’s commonly referred to as the climax in screenwriting and filmmaking happens here. This is where the protagonist faces the main antagonist or the primary conflict and it leads to a final resolution. Typically the climax is followed by an aftermath where we see how the protagonist’s life has changed as a result of what they’ve experienced.

Blake Snyder’s 'Save the Cat!' Beat System

Finally, there’s the late screenwriter and Save the Cat! author, Blake Snyder’s 15 beat system, which expands further on the three-act structure. It even goes as far as to give a page range for major beats:

Act I

- Opening Image: A moment or image that sets the tone.

- Theme Stated: Through dialogue or symbolism the story’s central theme is stated.

- Set-up [1-10]: Introduces the protagonist and their “ordinary world.”

- Catalyst: An event or conflict that disrupts the protagonist’s world and sets the story in motion (a.k.a. the inciting incident).

- Debate [12-25]: The protagonist questions whether to deal with the primary conflict.

Act II

- Break Into Two: The protagonist finally accepts the call to action and leaves their ordinary world to enter a new and uncertain one.

- B Story: The introduction of a subplot, often a new character, that will help the protagonist to grow and learn new skills. Many times, this gained knowledge also reflects the primary theme of the script.

- Fun and Games [30-55]: The protagonist and supporting characters face the story’s main obstacles and challenges with a mix of success and failure. Many times, these are the “trailer moments.”

- Midpoint: A major turning point where the stakes are raised after a false victory and defeat.

- Bad Guys Close In [55-75]: Things go further downhill for the protagonist and the “fun and games” are now soundly over as the obstacles increase.

Act III

- All is Lost [75]: The protagonist hits rock bottom; it looks like all hope is lost.

- Dark Night of the Soul [75-85]: The protagonist reflects on their loss and what faces them if they continue facing the primary challenge.

- Break Into Three [85]: The protagonist has a realization or epiphany where they figure out how to overcome the obstacles facing them (this oftentimes involves recalling something they learned earlier).

- Finale [85-110]: The protagonist takes action based on their new awareness, faces their biggest obstacle and defeats the antagonist(s).

- Final Image [99-100]: A concluding moment or image that mirrors the Opening Image, but shows how the protagonist has grown and changed.

Note: Final Draft has many structural templates you can use, including Save the Cat, Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, The Writers Journey and more.

Forge Your Own Path

Although there are various benefits to outlining before going to script, it’s important to not get lost in what should merely be a preliminary stage. Even if you’re using a beat sheet or beat board, it’s best to not be too locked into whatever structure you’re constructing.

A beginner screenwriter should follow basic three-act structure

and a few of the bigger and more essential beats cited by Blake Snyder (e.g. the Catalyst, Fun and Games, Midpoint, All is Lost). However, when it comes to the exact number of beats and every little moment being mapped out beforehand, you’ll likely suck any genuine inspiration from your writing and it can result in a stock or formulaic script.

Managers, agents and producers read scripts constantly and they are highly aware of all the standard beats and time-tested story tropes. As a result, your script might read too familiar or even be considered boring if you’re not throwing the occasional narrative or structural curveball. You shouldn’t try to reinvent the wheel, but at the same time, you shouldn’t simply be recreating someone else’s wheel.

Also, if you map-out your entire story beat-by-beat, you’ll likely come upon certain moments that ring contrived or untrue because your characters are being forced to abide by an imposed structure rather than reacting in a more organic and naturalistic fashion. The ideal beat sheet should be just as focused on and constructed around character as the plot they’re existing in. The strongest scripts are a combination of the right story with the right character, and allowing for some inspiration during the writing process. Think of your beat sheet or outline as a basic road map you follow while being open to an inspired detour or two.

So a beat sheet is essentially your first collection of ideas, strung together chronologically to create a basic framework to follow, and a preliminary stage before creating an outline and eventually going to script. Once you’re writing, however, it’s a whole other situation and you should be prepared to rethink and modify your beats along the way. A healthy balance between outlining and inspiration will help you finish your script and it will also make it a stronger one.