John Carpenter’s name has been synonymous with horror cinema since it first appeared above the title of Halloween (1978). His filmmaking prowess has spanned genres and influenced countless filmmakers, with movies that are easily identifiable from their moody, widescreen panavision cinematography, synth-heavy soundtracks that he himself often performs, and a penchant for slow-mounting dread and paranoia.

Across his films you can see and understand his fears and loves, from the frequent sieges on groups of strangers banded together, to the misfit, rebel protagonists determined to protect their individuality from the homogenized masses, and the recurrence of soulless villains amassing in mobs, lingering on the streets at night. While these themes and images all recur in his directorial work, it’s particularly distinct in the films that Carpenter wrote, often in collaboration with the likes of the great late Debra Hill, or his friends Nick Castle and Tommy Lee Wallace, both of whom had a turn playing “The Shape” in the first Halloween.

Carpenter sustained a long career by recognizing that if no one wanted to hire him to direct their movie, he’d just write his own and make it for cheap. Just in time for Halloween, here are the essential screenplays of John Carpenter.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)

Carpenter left USC before graduating, and expanded his stoney, sci-fi comedy student film into a feature called Dark Star (1974). Co-written with Dan O’Bannon, the shaggy film about a working class crew of astronauts had shades of a future O’Bannon screenplay, Alien (1979). It miraculously received a limited theatrical release, and while it would find a dedicated cult following over time, Hollywood didn’t come calling the way Carpenter had hoped for. He decided then, that the only way to get his next directing job would be to write a makeable script. One of the scripts he wrote eventually became Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), a horror/thriller set in the fashion world directed by soon-to-be The Empire Strikes Back (1980) helmer Irvin Kershner and starring Faye Dunaway. The final product bore little resemblance to Carpenter’s original screenplay, and his experience of receiving studio notes with which he disagreed only encouraged his desire to make his own film independently. That first independent film was Assault On Precinct 13 (1976).

In thinking about what sort of contained, low budget script he could easily direct, he thought back to the plot and character archetypes of his favorite westerns, like Rio Bravo, which featured a mismatched band of gunslingers protecting a jail from an army of bandits. With no expectation that he could get a traditional western made, he filtered the formula through the aesthetics of the more cost-effective exploitation films of the day, setting the siege at an abandoned LA police precinct and substituting street gangs for bandits. He called the screenplay 'The Anderson Alamo'. Austin Stoker plays a cop assigned to a police station that’s closing down, and Darwin Joston plays the cool, unflappable prisoner who he has to team up with to defend the titular precinct from a gang of almost alien-seeming criminals and their stockpile of stolen assault weapons.

The antagonistic LA street gang introduced Carpenter’s penchant for horror, more closely resembling the braindead zombies trying to break into the farmhouse in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1969) than western bandits. And instead of a backlot western town, Carpenter would shoot the streets of Los Angeles at their most desolate, in a run-and-gun action style similar to low budget cop thrillers like Gordon Parks’ Shaft (1971), and set the shoot-em-up second half on a soundstage for the precinct interior. Some USC friends used their connections to raise the $200,000 necessary to make the film, and Carpenter scored and edited it himself out of necessity. They struggled to shop the film to a distributor, in part because of a shocking early sequence where a gang member shoots and kills a little girl at an ice cream truck. Eventually, independent producer Irwin Yablans acquired distribution rights, and while the film underperformed in the US, after screenings at the Cannes Film Festival and other European festivals, it became a small hit overseas.

Already, many of Carpenter’s signatures were on display, like the silhouetted beings lingering outside in the night and cool-headed protagonists ready to receive them with a pithy one-liner. Having proven he could make a film, Yablans was anxious to find another low budget genre venture for Carpenter to helm. In the next theatrical film, there would be only one villain lingering in the street, wearing a haunting mask, and this time, his adversary wouldn’t be a cop. It would be a teenaged babysitter named Laurie Strode.

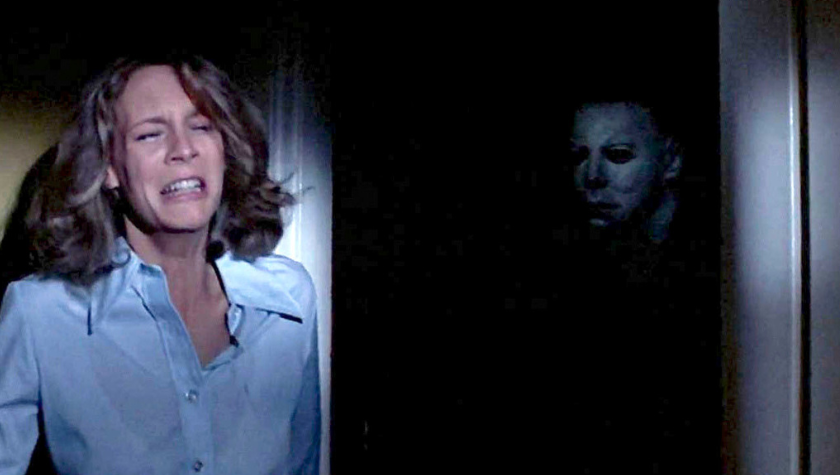

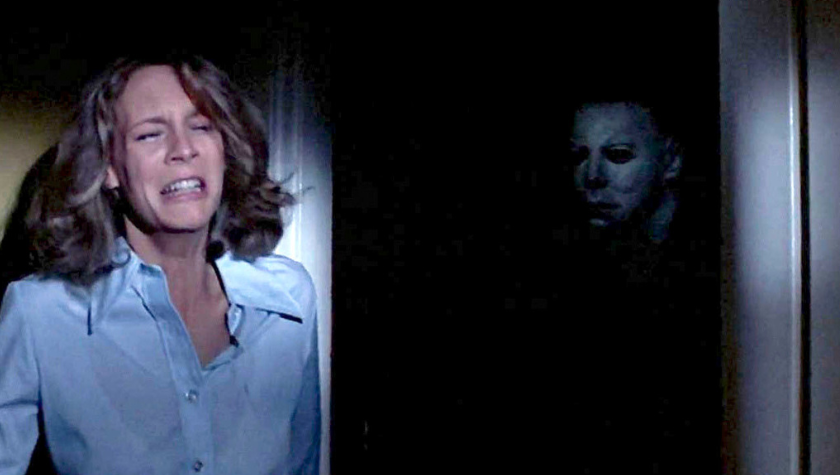

Halloween (1978)

Debra Hill, like Carpenter, had loved movies her whole life and also made Super 8 home movies as a kid. So when she found herself working as the script supervisor and then assistant editor on Assault, she and Carpenter hit it off. They began a romantic relationship that would only last a few years, but their creative collaboration would last for the rest of Hill’s life.

When Yablans decided he wanted to make a horror film after Assault, he enlisted Carpenter, and Carpenter enlisted Hill. Yablans’ idea was for a film where a killer would stalk and kill babysitters called 'The Babysitter Murders', and he knew Carpenter could make something of high quality on a low budget.

Given the budgetary limitations, Hill and Carpenter wrote a story that would take its time building tension and dread, integrating the audience into the lives of the characters while teasing out the arrival of the masked killer and limiting the onscreen violence until late in the film, leaving much of the carnage to the viewers’ imagination. Much of the natural dialogue and chemistry between the film’s teenage heroes can be attributed to Hill, while Carpenter chipped in more with the creation of the central killer, Michael Myers, a seemingly supernatural, walking manifestation of evil, and his distressed psychologist, Dr. Samuel Loomis, named for a character in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Another Psycho homage came in the form of Jamie Lee Curtis, an up-and-coming actress that Hill recommended because she was the daughter of Janet Leigh, the victim of the infamous shower murder in Psycho. Once Carpenter saw Curtis act, he knew she was perfect for the lead role of Laurie Strode.

Part of what makes the film so special is Hill and Carpenter’s script, which puts an emphasis on getting to know the characters through their joking and natural banter, so that the emotional stakes are higher when they encounter the horrors to come. Toward the end of a decade where the public was exposed to the violence of the Vietnam War and a rash of highly publicized real serial killings, Halloween’s horrors felt all too real.

The Fog (1980)

When Carpenter and Hill were in England to promote the British release of Assault, they took a trip to Stone Henge. There, Carpenter remarked on a thick bank of fog, imagining what sort of malevolent thing might be hiding in there. That idea became the basis for Carpenter’s first of a two-picture deal with independent production company, AVCO Embassy Pictures, The Fog (1980). Carpenter and Hill set about writing a screenplay that less represented the modern thrills of their recent slasher hit, and more the atmospheric chills of an old ghost story. They pulled from inspirations like Edgar Allen Poe, whose quote opens the film, the 50s British creature feature The Crawling Eye (1958), the real life shipwreck of the Frolic off the California coast, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), also about a malevolent force invading a small coastal town. In fact, they partially shot the film in Bodega Bay, where Hitchcock filmed The Birds, and the nearby Northern California town of Pt. Reyes.

The idea was that the ghosts of a century-old shipwreck would return to the town in the fog on the anniversary of their deaths, with an ensemble of townspeople facing the evil, from Hal Holbrook’s priest to Jamie Lee Curtis’ fearless hitchhiker. Curtis and the other women in the script, like Adrienne Barbeau’s cool, independent DJ with a cigarette hanging off her lip, are typically Hawksian, in the mold of Lauren Bacall or Angie Dickinson. This time, Curtis’ mother, the great Janet Leigh, even filled a role as a local real estate agent.

The Fog managed to be a minor hit, though it didn’t drum up the business or notoriety of Halloween. But because Carpenter had scaled up only slightly to a $1m budget, the film easily made a profit. For his second film in the AVCO Embassy deal, Carpenter decided to switch gears and genres, getting away from the shadow of Halloween by dusting off a non-horror script he’d written years earlier.

Escape From New York (1981)

In the mid-1970s, influenced by the public distrust of the American establishment in the wake of the Watergate scandal, and the image of New York as a criminal wasteland in the recent hit film, Death Wish (1974), Carpenter set about writing his own film that would pit Charles Bronson against a New York City wasteland, but with a sci-fi twist. He and Nick Castle collaborated in the writing of Escape From New York (1981), set in a future Manhattan that’s been walled off into a giant maximum security prison.

Hill produced the film, and in the role of Snake, Carpenter cast Kurt Russell. Carpenter met the former Disney child star when he directed him in the TV movie Elvis (1979), and thought it would be fun to cast Russell against type as the gruff, violent criminal, in the mold of Spaghetti Western antiheroes like Lee Van Cleef, who he also cast in the film. Ever influenced by westerns, Carpenter also borrowed a bit from the John Wayne film Big Jake (1971), in which various characters keep telling the hero they thought he was dead. With a bigger budget, Carpenter was able to build his most imaginative world yet, casting an ensemble of veteran character actors as various misfits who populated the future wasteland vision of Manhattan, and a clever use of visual effects from a crew that featured young James Cameron.

Escape became a box office hit for its high concept action premise and ever-relevant distrust of authority. The team would get back together to make a sequel years later, the more comic and satirical Escape From LA (1996), which not only reunited Carpenter and Hill as screenwriters, but added Rusell into the scripting process. After the success of Escape, Carpenter finally left the independent world to make a studio film when Universal offered him the chance to remake one of his favorite films, The Thing From Another World (1951). Resultantly, Carpenter didn’t produce an original screenplay of his own until necessity struck, six years later. And while The Thing is now considered among the greatest horror films of all time, its box office failure would kick off an up-and-down run of director-for-hire studio movies that ultimately left Carpenter back where he started, attempting to make an independent horror hit by writing for his supper.

Prince Of Darkness (1987)

After the box office failure of The Thing, Carpenter chose his next projects with a relative conservatism and an eye toward success. An adaptation of Stephen King’s Christine (1983), about a red Plymouth Fury that possesses its teenage driver, seemed a surer thing after the box office success of King adaptations Carrie (1976) and The Shining (1980). He followed it up by expanding his artistic palette with a more audience friendly sci-fi/romance, Starman (1984) and the martial arts action comedy Big Trouble In Little China (1986), but when that film became his second bomb at the box office after a tumultuous production, he became less enchanted with the studio system. Though all four of the jobs directing for studios are now beloved classics in their own right, Carpenter found himself unsure of what to do next.

The answer came in the form of Shep Gordon and Andre Blay, who were looking to court established filmmakers to work for their company, Alive Films. They offered Carpenter $3m and complete creative control on three different films, and Carpenter took the opportunity to refresh his artistic instincts and write a brand new project. Getting back to his horror roots and knack for low budget screenwriting, Carpenter pulled from a recent interest in quantum physics, and his love of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass films, in particular Quatermass and the Pit (1967). Unshackled from studio oversight, Carpenter unleashed a heavy, dread-filled nightmare called Prince Of Darkness (1987).

In the film, a priest played by Carpenter’s regular collaborator, Donald Pleasance, recruits a team of graduate students and scientists to investigate a large, glowing vial of slime that’s materialized in a church, and turns out to essentially be Satan. The film had every hallmark of Carpenter’s style; a healthy skepticism toward religion, a group of at-odds individuals trapped in a building under siege, zombified strangers slowly amassing on the streets outside, possessed by the Satanic pull, and an ending that’s hardly encouraging about the fate of man. Carpenter took the screenwriting credit of Martin Quatermass, to acknowledge his influence and keep his name from showing up in the credits too many times, and composed another stomach-shaking score of bass-heavy synthesizer to emphasize the slow-creeping, inevitable doom.

After a quartet of studio pictures, Carpenter’s first original horror film in years felt like one of his purest artistic statements. While the film wasn’t as acclaimed upon release as his biggest horror hits, it made a decent profit and announced the return of a horror master doing what he does best, with no creative shackles to stop him. For his second film with Alive, he’d once again do what he does best, and pivot completely.

They Live (1988)

Leaving behind the creeping dread of Darkness, Carpenter opted to channel his anger with the state of the country into a sci-fi/political satire film for his second Alive Films feature, adapting a short story called “Eight O’Clock In The Morning” by Ray Nelson. In the story, a man comes out of hypnosis to realize the world’s population has been hypnotized by an alien force through television signals. The story rang true to Carpenter during the money-obsessed Reagan 80s, and he set about adapting it into his most overtly political film, They Live (1988).

In order to make an alien invasion movie on a tight $4m budget, he decided that the aliens and subliminal messages they used to hypnotize the general public, would only be seen using a pair of special sunglasses. And given the weighty thematic subject matter, he’d abandon the dark tone of his last film for a more comic tone to help the message go down more smoothly.

They Live became another minor box office hit before ultimately achieving a large cult audience, in part due to its iconic imagery and eternally relevant political messaging, but Carpenter had a falling out with Gordon and Blay before they could successfully put together a next film. Resultantly, Carpenter wound up taking as much time between movies as he ever had, before winding up with another for-hire job directing the Chevy Chase comedy vehicle, Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992). He’d honor his third film with Gordon and Blay by giving them Executive Producer credits on a remake he directed of Village of the Damned (1995), and directed the undersung Lovecraftian masterpiece, In The Mouth of Madness (1994) in between, from a script by now CEO of Warner Bros. Motion Picture Group, Michael De Luca. And while he exercised his writing craft once again with Hill and Russell on 1996’s Escape sequel, it wouldn’t be until 2001 that he wrote another original horror film, one that harkened back to his very first forays into screenwriting. What no one knew at the time, is that it would be his final produced screenplay.

Ghosts Of Mars (2001)

After directing the hit action-horror film Vampires (1998) for Sony, they wanted to be in the John Carpenter business, and offered to make another film with him under their Screen Gems banner. With the promise of a decent budget and complete creative control, Carpenter took to writing what would be his last produced screenplay, which he recruited his friend, Larry Sulkis to co-write. It’s fitting then, that the resultant film, Ghosts Of Mars (2001), plays like a summation of many of Carpenter’s life-long obsessions, like the dream movie he would’ve thought up at the cinema as a boy in the 1950s.

He’d always wanted to make a movie set on Mars, but like with Assault and Escape, he gave his Mars setting a western movie aesthetic and plot. As a final ingredient, the master of horror couldn’t help but make the villains into mutilated, possessed humans, inhabited by violent Martian ghosts. He finished it off with an original score that not only featured his typical synthesizer themes, but hard-hitting heavy metal to accompany the action with guest musicians like Anthrax and Buckethead.

Much like in Assault, the film pits a cop against a criminal, with the two ultimately having to team up and battle a greater evil in order to survive. As with Carpenter’s core texts, the true horror comes in the form of losing free-thinking individuality, of brain-dead conformity to a homogenized, dominating group. Like the monster in The Thing, the Satanically possessed victims of Prince of Darkness, or the alien-controlled citizens of They Live, the victims in Ghosts have all lost themselves to a sinister force, and the fate worse than death for our heroes would be to become one of them, to lose all individuality. And like in his best films, those who survive need to overcome their differences to fight the pervading evil.

Bucking the system to remain John Carpenter

Carpenter now works on comic books and music with various members of his family, and regularly appears at fan cons and screenings, but whenever asked if he’ll make another film, he expresses total contentment with what he’s done, and with letting the next generations do what they do.

What’s remarkable about John Carpenter’s career is how often his ambitions were more about a love of cinema than about a pursuit of money. Whether it was trying to break in, or when he became disenchanted with the system, he would always take to the page and write a movie he’d want to see, that was personal to him, and that he could make either outside of the system, or trick the system into making. No matter what the trends or politics of the day dictated, John Carpenter always remains John Carpenter.