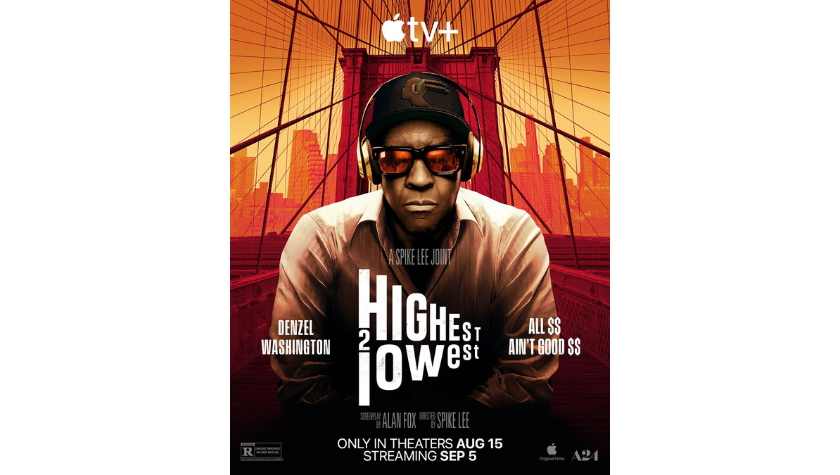

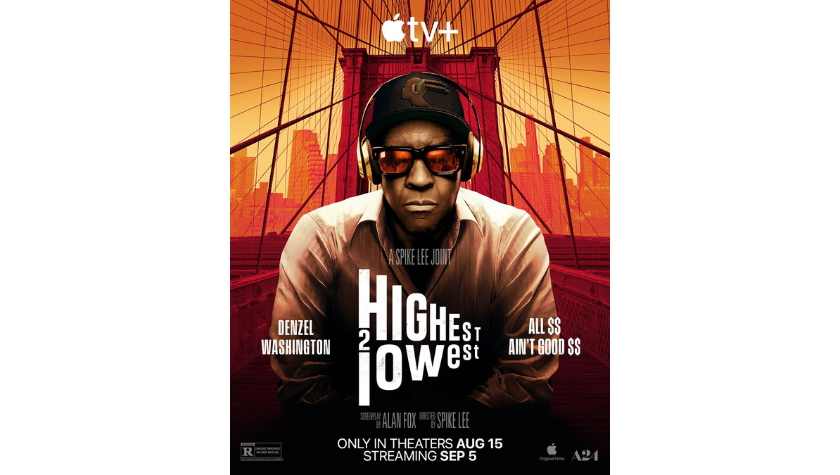

With Spike Lee’s newest film, Highest 2 Lowest, the acclaimed New York director not only reteams for the fifth time with his Academy Award-winning muse, the great Denzel Washington, but joins a lineage of distinguished filmmakers who have adapted the works of legendary Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa.

The new film is a reimagining of Kurosawa’s 1963 classic, High and Low, about a business tycoon thrown into a moral crisis when his chauffeur’s son is kidnapped and held for an enormous ransom. Kurosawa adapted the original film from a police procedural book written by New York crime author Evan Hunter, reinterpreting the text to add a deeper pathos and exploration of class in a changing post-war Japan.

But this was far from the first time Kurosawa had adapted a film from previous works of western pop culture. Frequently collaborating with screenwriters like Hideo Oguni, Shinobu Hashimoto and Ryûzô Kikushima, Kurosawa found influence for his samurai films, dramas and contemporary thrillers alike in American suspense yarns, John Ford westerns and the plays of William Shakespeare (Throne Of Blood (1957), The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and Ran (1985) all owe a debt to The Bard). While Kurosawa was always generous in crediting his influences from across the globe, his acclaimed films are unique in how often and in what a broad range of filmmaking styles they’ve been reinterpreted as well.

From a star-making 1960s spaghetti western to a recent low-key British Oscar nominee, Kurosawa’s storytelling fingerprints have echoed through history, across countries and genres. Even filmmakers who haven’t remade his films explicitly, like George Lucas and Martin Scorsese, are still quick to acknowledge the extraordinary influence his cinema has had on their work.

By filtering aspects of Hollywood genre cinema and western literature through his own culture and distinct cinematic language, Kurosawa became an international star, and subsequently reinvigorated countless western storytellers. In studying Kurosawa’s influence, one finds an ever-lengthening daisy chain of inspirations and remakes whose links have traveled the better part of a century to arrive at one of this year’s most high profile films by a modern master in his own right.

Here are 7 English-language reinterpretations of the great Japanese master, Akira Kurosawa.

1. The Magnificent Seven (1960 & 2016)

Among the Hollywood films Kurosawa was influenced by at a young age were American westerns and particularly those of John Ford. The genre and its key filmmaker mythologized the past and the idea of the noble warriors who populated it in a way similar to the samurai films of Japanese cinema. When in his research on samurai history Kurosawa came across stories of samurai defending farmers, he saw the perfect framework to create an exciting samurai adventure in the mold of a western. The resulting film, Seven Samurai (1954), is about villagers who hire the titular heroes, portrayed by such Kurosawa regulars as Toshirô Mifune and Takashi Shimura, to defend them from bandits. It became a breakout hit, outgrossing the original Godzilla (1954) to become the highest grossing Japanese film of the year, winning the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion award, and getting nominations at both the Academy Awards and the BAFTAs. The US release was retitled The Magnificent Seven, but when Hollywood went after remake rights, that title would be repurposed for a brand new film.

The team-building structure, where Shimura’s character goes around to recruit a group of samurai, has been repeated in wide-ranging films from Ocean’s Eleven (2001) to Avengers: Endgame (2019), but the first official Hollywood remake naturally converted the same structure into a western. The remake rights passed through several hands and script drafts until the late 50s, when The King and I (1956) star Yul Brynner signed on to the lead role under the direction of western regular John Sturges.

In the Sturges biography Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges, producer Walter Mirisch describes a screening of Samurai with Sturges as “One of the most stimulating experiences I’ve ever had in this business. I can still see us sitting there, shouting back and forth. As it played out, we translated it into Western terms. We re-imagined it.” An all star cast of budding stars from Steve McQueen to Charles Bronson joined Brynner on the team of gunslinging samurai surrogates, defending a Mexican village from bandit Eli Wallach. And while the starry cast and shoot-em-up thrills have since made it a beloved classic of the western genre, critics at the time saw it as a shallow Hollywood treatment of the original Japanese masterpiece, with all the poetry and elegy sanded away. It did, however, make a splash overseas, and became a huge hit in Europe, a continent on which the next Kurosawa-inspired Western would emerge just a few years later.

While the international success of the film spawned several sequels and a TV series, it took until 2016 for there to be a proper remake. Denzel Washington took the lead role that Brynner had once occupied, reteaming with his Training Day (2001) and The Equalizer (2014) helmer, Antoine Fuqua and their former collaborator, Ethan Hawke. International stars from Chris Pratt to Lee Byung-hun fleshed out the rest of the seven, and Fuqua’s reliably muscular action direction made for a fun-filled audience ride that grossed $162m world wide. The film’s success proved the timelessness of Kurosawa’s then 60-year-old plot structure, a testament to the universal language of sturdy cinematic storytelling.

2. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

While Hollywood was trying to spin gold out of Seven Samurai, it was in Italy that writer/director Sergio Leone was planning his own Kurosawa western remake that would spawn an entirely new subgenre. In 1961, Kurosawa directed Yojimbo, starring Mifune as a lone ronin swordsman who comes upon a town torn apart by warring gangs. Kurosawa cited the influence of film noir The Glass Key (1942), based on the Dashiell Hammett novel, while critics have noticed greater similarities to the Hammett novel Red Harvest wherein the protagonist, the Continental Op, navigates a gang war in a Montana mining town. The action-packed loan wolf adventure film became another international hit, garnering an Oscar nomination for its costumes and a Best Actor award for Mifune at the Venice Film Festival, where Kurosawa was once again nominated for the Golden Lion. It was upon its release there in Italy that Leone became inspired to adapt the story into a western film, marking his second credited directorial effort.

Upon seeing Yojimbo, Leone immediately recognized the archetype of the wandering gunslinger through fresh eyes and reportedly watched it over and over on a moviola to fully understand its structure. He decided to extract the Western story from the Japanese film, and shoot it with an Italian crew in the Spanish desert. What brought the film all the way back around to its American DNA was the inclusion of American television actor, Clint Eastwood, then best known for his supporting role in the western series Rawhide (1959). While he would’ve preferred to get a starring role in a big Hollywood film, Eastwood skeptically went to Europe to fill the Mifune role, unaware that it was his Fistful character, The Man With No Name, that would ultimately make him into a star and cinematic icon.

Using his now legendary, deliberately paced builds of tension and alternating close-ups, and the great Ennio Morricone composing an unforgettable score in the style of Hollywood westerns, Leone created A Fistful Of Dollars (1964). The film’s distinct style is often credited with solidifying the Spaghetti Western genre designation, and kicked off a trilogy that concluded with The Good, The Bad & The Ugly (1966). The finished trilogy took the world by storm due to its bold new style of an old genre, and Eastwood’s counterculture appeal. Unfortunately for Leone, Yojimbo rights holders Toho Studios sued him. At least he could pride himself on receiving a complimentary letter from Kurosawa that read, “I’ve seen your movie. It’s a very good movie. Unfortunately, it’s my movie.”

A Fistful of Dollars is perhaps the foremost example of how Kurosawa transformed international cinema. An Italian filmmaker inspired by a Japanese filmmaker inspired by American filmmakers managed to create an entirely new style of moviemaking that would influence future cinematic movements, and it couldn’t have happened without the conversation happening between far-flung nations in this new post-war cinematic moment. While the archetypes of these films would be endlessly replicated, this particular story would finally receive an official American remake, set in the gangster world, 30 years later.

3. The Outrage (1964)

Prior to the success of Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, a young Kurosawa broke out onto the world stage in a big way with what many consider his masterpiece, Rashomon (1950).

Based on two stories by prolific Japanese author Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, the film tells the story of the murder of a samurai and assault of his wife, through several different contradictory testimonies and points of view, with differing details and motives from each. Kurosawa’s film explores the nature of truth and the subjectivity of human memory and experience, the basis for a phenomenon now known as “the Rashomon effect.” The bold storytelling technique and complex, weighty themes made it a breakout hit, and the first of Kurosawa’s films to receive US distribution. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and an honorary Academy Award, establishing Kurosawa as an internationally renowned filmmaker.

The popularity of Rashomon put it at the forefront of a new explosion of post-war international cinema that included the Italian neorealists and French New Wave filmmakers, and its influence is as vital as ever, with Ryan Reynolds revealing that his original pitch for Deadpool & Wolverine (2024), of all movies, was based on Rashomon. But the first official remake of the film came in the wake of the other Kurosawa western remakes, with Martin Ritt’s The Outrage (1964).

Scripted by Michael Kanin, based in part on his short-lived 1959 Broadway adaptation of Rashomon, The Outrage translates the original plot to the 1870s Southwest, with Paul Newman miscast as the Mexican bandit who’s accused of perpetrating the crimes. While Ritt was responsible for such Newman classics as Hud (1963) and Hombre (1967), The Outrage received poor reviews, comparing it negatively to the greatness of Rashomon, and the film has become largely forgotten now. The shadow of Rashomon, however, looms large, and would influence a great many films, including the debut feature of future Kurosawa acolyte, Spike Lee.

4. Runaway Train (1985)

In 1966, Kurosawa ventured into English-language filmmaking with an adaptation of a 1963 Life Magazine article by Warren R. Young called The Runaway Train with the subheading: “Real nightmare: a lone man’s juggernaut ride at 89mph.” The true story of a runaway train in Syracuse, New York struck him as a perfect thriller premise, and he made a deal with Embassy Pictures to shoot the film in 1966. Sidney Carroll, who received an Academy Award nomination for writing the screenplay for Newman vehicle The Hustler (1961), wrote the English language adaptation of Kurosawa’s script. It tells the story of two escaped convicts who hide out aboard a train going over dangerous, snowy terrain, when it speeds out of control. Bad weather in New York stalled the production twice, and after Kurosawa experienced creative differences working on the Japanese portion of the American-Japanese co-production Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), an epic spectacle about the attacks on Pearl Harbor, he abandoned his ambitions to work in Hollywood and returned to Japan.

The script bounced around for years until it found financing from The Cannon Group in the 1980s. Francis Ford Coppola, a friend of Kurosawa’s, recommended Andrei Konchalovsky, a writer/director known for his collaborations with Russian arthouse legend Andrei Tarkofsky, to direct.

“The design is still Kurosawa’s,” Konchalovsky told the New York Times in 1985, “The concentration of energy and passion, the existential point of view, and the image of the train as something - perhaps civilization - out of control. I was extremely cautious in protecting Kurosawa’s main design.” Jon Voight and Eric Roberts took the lead roles in what became an adrenaline-fueled, snowbound action spectacle, and Runaway Train (1985) competed for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and garnered Academy Award nominations for both of its leads. While the film failed to become a box office hit, it remains a much lauded classic of the action genre, with few realizing that the project originated with the great Kurosawa at the height of his creative powers.

5. Last Man Standing (1996)

Screenwriting legend Walter Hill has often cited Kurosawa as one of his favorite filmmakers, so in 1996, when he learned that Kurosawa was supportive of an American remake of Yojimbo, he agreed to take the job. Rather than make another western like Fistful, Hill decided to adapt it to yet another genre, a Prohibition-era 30s gangster movie called Last Man Standing (1996). He cast Bruce Willis, one of the biggest stars of the 90s, in the wandering loner role that Mifune and Eastwood had played so iconically before him. In this iteration, John Smith, as Hill named the character, comes across a mob war in a Texas bordertown. Hill had created several iconic, wordless loaners to great acclaim in movies past, like Charles Bronson’s bareknuckle boxer in Hard Times (1974) or Ryan O’Neal’s getaway driver in The Driver (1978), and with well-established action chops and Bruce Dern and Christopher Walken in supporting roles, the film had all the right ingredients to be a classic.

Critics were cool on Last Man, however, and it failed to recoup its budget at the box office, perhaps due to the more stoic tone that Hill applied in the vein of his arthouse predecessors during a time when blockbuster bombast was more in fashion. But Hill was true to the Kurosawa and Leone lineage in that he attempted a mythical tone in regards to his lead character, one that many filmmakers have used in their own distant homages to Kurosawa’s wandering loner.

Elsewhere in the 1990s, Luc Besson’s Léon: The Professional (1994) and Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) were among the modern classics that echoed the archetypes of Yojimbo. Even today, John Wick helmer Chad Stahelski has mentioned Kurosawa as an influence on his own iconic hero.

6. Living (2022)

Kurosawa found inspiration in Tolstoy’s 1886 novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, when conceiving of Ikiru (1952), a drama released smack dab in between Rashomon and Seven Samurai. Kurosawa mainstay Shimura plays a Japanese bureaucrat in the film, who receives a terminal cancer diagnosis and begins looking for meaning in his life, and ways to make his existence valuable before it’s too late. The film, whose title translates to “To Live,” poses profound questions about what it means to truly live, and upon release, continued a streak of critical acclaim for Kurosawa. To this day, the film regularly appears on lists of the greatest films of all time, and was counted among the favorite films of Roger Ebert.

Sixty years after Ikiru’s release, British actor Bill Nighy was asleep on his couch when friend and collaborator, producer Stephen Woolley, called to remind him that he was late for a dinner whose guests included Nobel Prize-winning writer, Kazuo Ishiguro. Nighy rushed over and the two got along so well that by dinner’s end, Ishiguro had decided he wanted to reimagine Ikiru with Nighy in the lead role. Ishiguro’s script transposed the story to 1950s London, where Nighy’s British bureaucrat is forced to reckon with a terminal cancer diagnosis, as in the original. Under the gorgeous direction of South African director Oliver Hermanus, Living (2022) distinguished itself from the original with its unique style and setting, while maintaining a quiet, profound power that was all the more resonant in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

It received critical acclaim and garnered Academy Award nominations for both Nighy and Ishiguro, all stemming from that seemingly unremarkable dinner party where a group of creatives waxed poetic about film history. It’s a testament to the themes of Kurosawa’s works that a story like Ikiru can transcend time and place and fit into a contemporary film with just as much resonance as it had sixty years ago. Like the swashbuckling heroism of Kurosawa’s samurai films, his ruminations on universal themes of death and regret in Ikiru, proved absolutely timeless.

7. Highest 2 Lowest (2025)

Spike Lee discovered Kurosawa during his time at New York University, and cited Rashomon as an influence on his debut film, She’s Gotta Have It (1986). The film explores the character of Nola Darling through the points of view of three of the men she’s dated in a structure inspired by the Kurosawa film. So when Denzel Washington attached to play the Mifune role in a US remake of Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) set in New York City, and offered Lee the directing role, the Kurosawa super fan jumped at the opportunity. Washington plays a record executive instead of a shoe manufacturer, giving the film a musical bent. While Kurosawa’s original is known for its meticulous, deliberate staging and clockwork pace, Lee does as only Lee can do, and tells the story with a messy vibrancy reflective of the rhythms of New York City, which the kidnapping thriller speeds through with a jazz-like spontaneity and colorfulness.

In fact, Lee has compared his treatment of the original text to a jazz cover version of a standard, like John Coltrane’s jazzy reworking of “My Favorite Things” from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, The Sound Of Music. Rather than reverently try to recreate the Kurosawa film, Lee takes the core story and riffs on it with the same playfulness and experimentation that’s put him at the forefront of filmmaking for 40 years. His is a perfect analogy for the way Kurosawa’s influence continues to permeate cinema and culture at large today. Kurosawa’s films made such an impression on the world, that filmmakers of all nations and genres can’t help but make work in conversation with his structures and themes, dressing them up in new clothes and cultures to make their own modern classics.

The phenomenon of both the influences on Kurosawa’s work and Kurosawa’s eternal influence on generations of filmmakers, teaches us two valuable lessons. First, it’s so important to experience stories, movies, art and culture from all over the world, even the most seemingly distant of places, as evidenced by both Kurosawa’s love of work from other places and times, and the way Kurosawa’s work has impacted western culture. Second, the foremost reason that Kurosawa’s films are still being remade today is because they were about characters and themes that meant a lot to their filmmaker and truly reflected the human condition in a way that’s personal and universal enough to have lasted almost 30 years after his death. The art of cinema is a global language, and by leaving no stone unturned in terms of finding influence, contemporary filmmakers can find new and exciting ways to convey their core truths.

Highest 2 Lowest is now streaming on Apple TV+, and the works of Kurosawa can be widely seen, not only streaming on HBO Max and The Criterion Channel, but on the big screen in current theatrical retrospectives at the Prince Charles Cinema in London, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles, and the Film Forum in New York City.