Technically speaking, montages are more the domain of an editor, splicing together different scenes to illustrate a passage of time. Montages, however, became such a fixture in the cinematic vocabulary that it’s not unusual to find them in screenplays. It’s not wrong to do so, and there was a time in which pretty much every script had at least one montage.

But, as with many techniques, it can be overused and abused.Also, montages aren’t particularly fashionable at the moment.

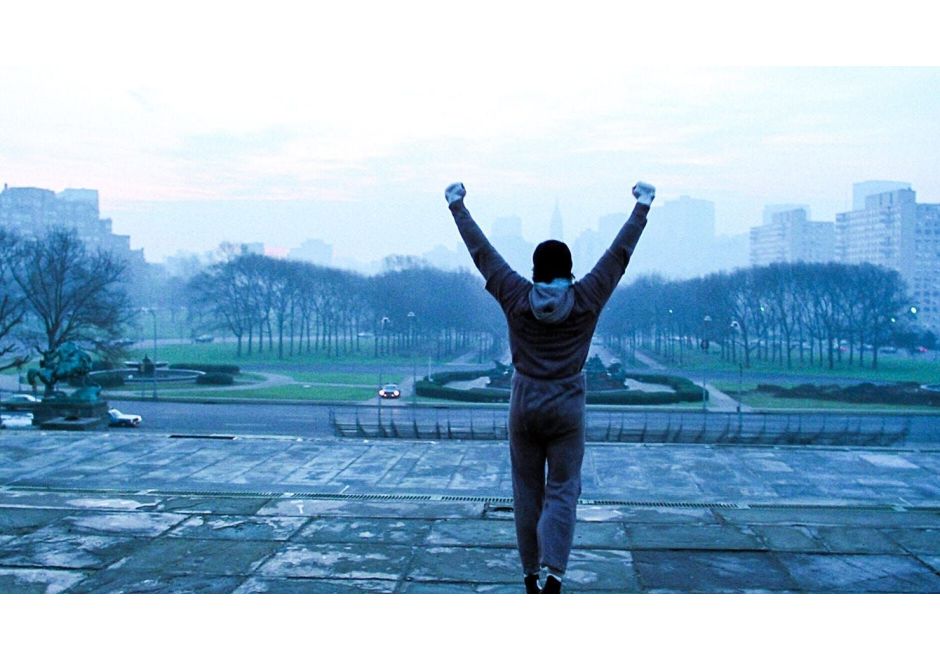

This is largely due to them being so heavily used in the 1980s that montages can come across as parodic. Perhaps the most famous montage is the training sequence in 1976’s Rocky. It not only led to similar training montages in the Rocky sequels, but many films in the 1980s featured a scene of the protagonist either physically training or working toward a goal to a popular song (usually accompanied by a synthesizer and inspirational lyrics). As a result, if you utilize a montage in this fashion, it may come across as a 1980s’ spoof.

Character-driven montages, as opposed to goal-driven montages, haven’t been used to the point that they’re parodic. A good example are the montages in Taxi Driver in which we see various shots of Travis Bickle driving through the city as a voiceover conveys his thoughts. The montages in this context are used to reveal Bickle’s worldview and growing psychosis. It also gives you a sense of his job: driving, night after night, in a decaying city.

The most common and straightforward use of a montage is to show a character making his or her way from one location to another. In a road-trip film, it’s more or less guaranteed you’ll see a montage. This is general enough to not come across as parodic (unless you use Lindsey Buckingham’s “Hollywood Road” as a soundtrack cue). Road trips themselves have been played out in recent years but, unless it’s a contained thriller, sometimes a character needs to get from Point A to Point B. And if it’s a long journey, spanning several days, a montage can be your best way of conveying the trip and passage of time.

But how does one write a montage in a screenplay?

{{cta('63226993-7045-4192-8aec-aa34ea838678')}}

There’s no set format, so sometimes it’s just up to what you think looks good on the page.

In place of the slug line, you can simply write “BEGIN MONTAGE” or “CUE MONTAGE”. Maybe offer up a line of explanation of what we’re seeing visibly (e.g., “We see various shots of Pierre making his way across the French countryside”) and then just list the shots. Don’t have a scene heading for each shot. This would take up way too much page space. It’s understood that these are flashes of locations and not full scenes. In fact, it’s not a montage at all if you break up every shot with a scene heading; it’s then just a bunch of very short scenes juxtaposed. What makes it a montage is you’re describing a visual technique. Anyone who can help you in your career will immediately know what a montage is and what you’re going for. Just list the shots as simply, yet vividly, as possible.

When I first started writing screenplays, I numbered the shots like this:

1.) Junior and Ray carry a PLASMA TELEVISION from the frat house to the Dodge Dart.

2.) Junior and Ray hop into the Dart.

3.) The Dart peels out.

4.) The Dart drives away from the college campus and onto the highway.

At the time, this wasn’t uncommon (a few people even used letters as opposed to numbers).

But, over the years, numbering (and especially lettering) became viewed as overkill.

These days, a simple dash is best. Let’s revise the above montage and now use dashes instead of numbers.

- Junior and Ray carry a PLASMA TELEVISION from the frat house to the Dodge Dart.

- Junior and Ray hop into the Dart.

- The Dart peels out.

- The Dart drives away from the college campus and onto the highway.

See? You didn’t lose anything by losing the numbers.

If anything, the dashes are less distracting and force the eye to focus on the description and action.

In regard to length, the shorter the better. Simply list the shots that convey vital information and move the story forward. If your montage is more than a page long, readers are going to get impatient.

Like any oft-used cinematic technique, montages can come across as parodic or hackneyed.

But used sparingly, they can be useful and give your script motion.