What Is Subtext in Screenwriting?

Subtext is one of the defining tools of sophisticated screenwriting.

It’s what separates on-the-nose dialogue from layered character work. It’s what allows a scene to feel charged without anyone saying a word. And it’s often the difference between a screenplay that feels written and one that feels lived. If escalation is the engine of a story, then subtext is the current running beneath it.

Yet many screenwriters misunderstand subtext. They treat it as vagueness. Or withholding. Or simply “not saying the obvious thing.” But subtext is not about hiding information: it’s conveying meaning beneath the surface.

It’s what a character really wants, fears, or believes — expressed indirectly. Characters argue about one thing while really fighting about something else. The characters might not know it, but if subtext is effectively conveyed by the writer, the reader or audience is also clued-in.

In literature, subtext often lives in the interiority — narration, metaphor, internal thought. In film and television, subtext is behavioral. It lives in performance, framing, silence, gesture, and contradiction between words and action.

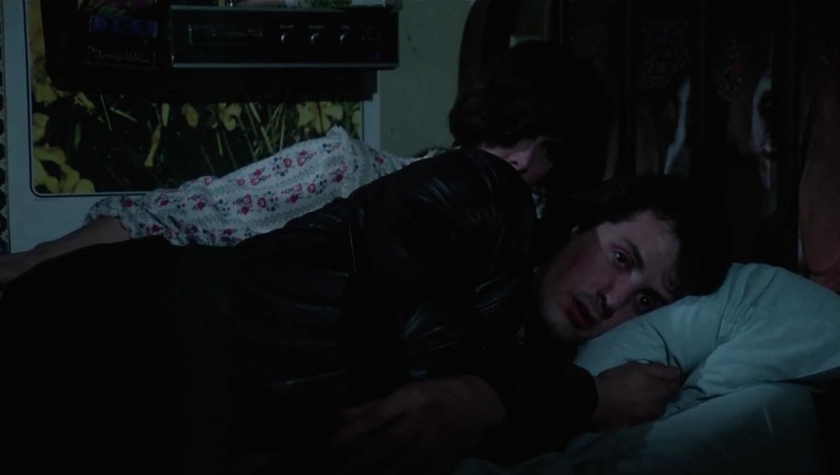

Consider the classic parlor scene in Psycho.

On the surface, Norman Bates is discussing taxidermy, loneliness and the obligation he feels for “Mother” with Marion Crane. The conversation appears polite if slightly awkward. Underneath, Norman is grappling with suffocating control and suppressed rage. His references to traps and stuffed birds are not casual hobbies: they are metaphors for domination and psychological imprisonment.

The scene works not because of what is said.

It works because of what is implied.

Why Subtext Resonates

Subtext resonates because human communication is rarely literal. People protect themselves. They posture. They deflect. They hide vulnerability behind sarcasm, professionalism, or sometimes even aggression. When dialogue reflects this truth, it feels authentic (referred to as naturalistic dialogue in screenplaywriting).

In addition, subtext allows the reader or audience to participate. They decode. They interpret. They sense there’s something deeper going on. That act of participation creates emotional engagement: an ideal goal for any writer.

Subtext also respects the intelligence of the audience. Instead of explaining emotion, it allows viewers to infer it. That inference builds further investment.

Think of the movies and TV shows that connected with you: didn’t you feel more involved when truth was reflected and you figured things out for yourself?

If you can create a similar response via your script, it’ll connect with more people.

How To Inject Subtext into Your Screenplay

Subtext doesn’t appear accidentally. It’s created on the page.

Here are some basic ways to inject subtext into your screenplay:

1. Separate External Goal from Internal Goal

Your protagonist’s external goal should be fueled by an internal goal. On the surface, they pursue tactical objectives. Underneath, they pursue emotional objectives.

For example, throughout Rocky, Rocky Balboa is focused on survival, training for his heavyweight match and courting Adrian. However, towards the end of the film, Rocky confesses his true goal is proving he’s not “just another bum in the neighborhood.” He wants to be a man who is both worthy of his heavyweight match and Adrain’s love.

2. Know Your Characters' Hidden Desires

Before writing, identify what the character truly wants in the scene — and what they are unwilling to say out loud. If a character says, “I’m happy for you,” but internally fears abandonment, the line becomes loaded. Even if it’s unsaid, your knowledge of your character’s desires will seep through.

Rocky’s line about not wanting to be “just another bum” lands because of all the frustration and longing built up prior to its utterance. When writing Rocky, Sylvester Stallone knew his character — very much a reflection of himself — and as such he knew Rocky’s hidden desires.

3. Use Behavioral Contradiction

Subtext thrives in contradiction between what is said and what is done. If a character insists they’re calm while breaking a glass, the behavior reveals the truth. Throughout Breaking Bad, Walter White always presents himself as a man of reason with a logical and methodical approach to his criminal activities. However, as the series progresses, despite Walter’s careful and analytical language, it becomes clear he’s a man violently brimming with anger and resentment. Despite his numerous justifications and reasoning, Walter is ultimately acting out darker, sociopathic impulses.

4. Use Environment as Suggestion

Although a character’s dialogue and actions are common ways to inject subtext into your script, it can also be conveyed by the setting and environment. Think of the shadowy world of a film noir where dark secrets are suggested without a single word being uttered.

Batman and Commissioner Gordon don’t have to tell us Gotham City is teeming with crime and corruption. In The Godfather, Vito Corleone’s dimly lit office lets us know that beneath the civility of the meetings there are darker things at play. When worldbuilding, take the opportunity to add another layer of subtext.

Subtext Reinforces Theme

The above suggestions are ideal for beginner screenwriters, but perhaps you want to take things to the next level and add even more subtext to your script.

This is when it’s time to step back and examine the theme you’re working with. A theme answers the question: What is this story about beneath the plot?

This question is subtextual in nature. Subtext reinforces theme and vice versa. They are reciprocal. The deeper your theme, the deeper your subtext should be.

In Mulholland Drive, characters rarely articulate what the story is actually about: identity, illusion, ambition, rejection, the brutality of Hollywood mythology.

Plot-wise, the film presents a mystery: amnesia, auditions, strange encounters, fragmented events. But the two primary themes are fractured identity and the psychological collapse that follows failed aspiration. Betty’s optimism in the early sections feels sincere. Her audition scene is electric, confident, almost intoxicating. On the surface, she is a talented newcomer navigating Hollywood. The truth, revealed later through Diane, is she’s delusional.

The most powerful use of subtext in Mulholland Drive isn’t within individual scenes — it’s structural. The first half of the film operates as wish-fulfillment fantasy. The second half reframes it as psychological aftermath. The subtext of ambition and rejection isn’t hidden inside dialogue alone. It’s embedded in narrative form. The story itself becomes subtext.

The film doesn’t explain its theme: it buries it inside identity shifts and behavioral contradiction. If your screenplay’s theme only appears in speeches or climactic monologues, it isn’t integrated. True thematic cohesion comes when subtext reinforces the theme invisibly. Every argument, every silence, every hesitation should echo the central idea of your story.

Inject Subtext into Every Story Beat

Diving even deeper, you can inject subtext into every story beat. You should definitely consider this if you’re writing a drama, social satire or slow burn thriller. Think of subtext as the low flames steadily bringing your characters’ mounting conflicts and secret desires to a boil.

In The White Lotus, nearly every conversation operates on two levels. On the surface, characters discuss vacation plans, spa treatments, dinner reservations, or minor inconveniences. Underneath, they’re negotiating power, status, class, sexuality, and resentment.

In season one, the room dispute between Shane and Armond appears logistical. A booking error. A suite mix-up. But the subtext is entitlement versus barely concealed contempt. Shane frames himself as reasonable. Armond presents himself as professional. Every exchange escalates because the real conflict isn’t about a room — it’s about dominance and humiliation.

In season two, Harper and Ethan’s marital tension unfolds through arguments about behavior and social discomfort. They debate awkward dinners and sexual frequency — yet the subtext is fear of stagnation as they approach middle-age and further commitment.

In season three, brothers Saxon and Lachlan’s relationship is entirely fueled by subtext as they attempt to mask their insecurities and need for connection with prototypical male bonding. Saxon plays the role of alpha older brother, instructing Lachlan on girls, sex, and protein shakes — all the while something more complicated and twisted is waiting to manifest between them.

What makes The White Lotus dramatically compelling isn’t plot. It’s subtextual escalation. Characters rarely articulate what they actually mean. Every beat carries double meaning. Yes, each season there is a mystery death to pull us in, but there are numerous other time bombs we’re waiting to see go off: every character, an impending catastrophe. This is possible because of the subtext writer and showrunner Mike White injects into every single scene.

Mastering Subtext in Screenwriting

Whether it’s a feature screenplay or a television pilot, there are various ways to add subtext to your script: separating external goals from internal goals; knowing your characters’ hidden desires; behavioral contradiction and suggestive environments. Also using subtext to reinforce your theme and injecting it into all of your story beats, will help you create something that sticks with readers.

If you want your screenplay to feel sophisticated, emotionally resonant, and dramatically layered, mastering subtext isn’t optional.

It’s essential.

Because the most powerful moments in a story aren’t spoken.

They’re understood.