Animated movies consistently rank among the top-grossing films of the year, drawing large audiences, breaking box office records, and generating substantial merchandising revenue.

Obvious hits like Inside Out 2 bring in massive global box office hauls, and franchises like Zootopia have surpassed $1 billion worldwide, underscoring the long-term financial power of animated storytelling. Meanwhile, anime releases such as Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train reinforce the global earning potential of animation, with more than $500 million worldwide, including over $45 million in the United States.

When you factor in ancillary revenue streams like consumer products, streaming, and international markets, animated films can reach even greater financial heights, proving that animation is not just family entertainment, but a major force in the global film business. Ever since Space Jam in the 1990s, the marriage between sports and animation has been a consistent winner, as seen in movies like Cars, Rumble and Surf’s Up.

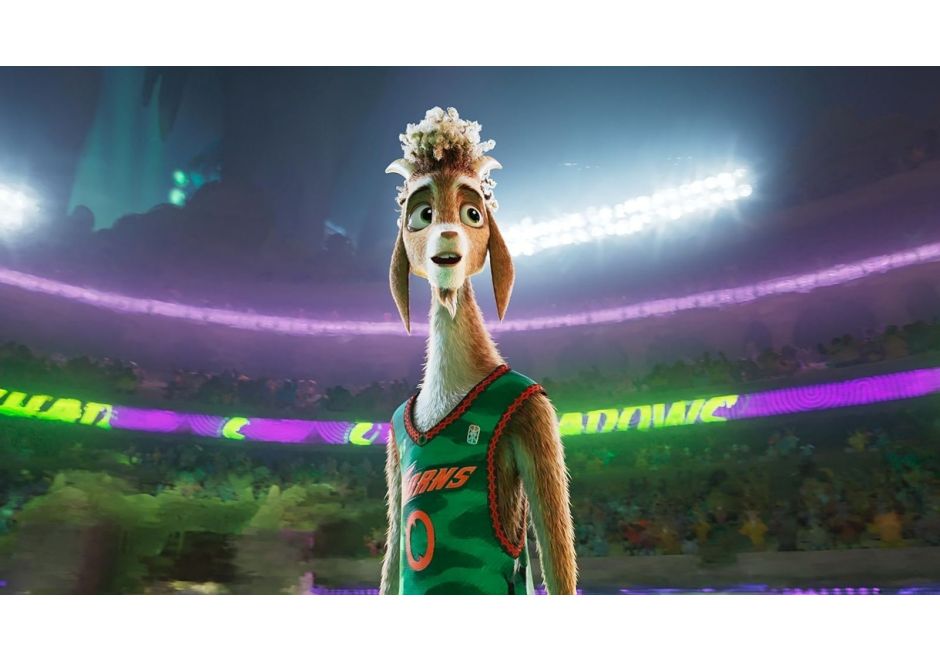

The latest iteration of the animated sports story is GOAT, which is both a play on the Greatest of All Time (GOAT) and the fact it’s a goat playing a version of basketball, with one of the main characters voiced by basketball great Stephen Curry, who also produces.

GOAT follows Will Harris (Caleb McLaughlin), a young roarball (a sport similar to basketball) player with aspirations of joining his home team led by legendary player Jett Fillmore (Gabrielle Union). The epitome of an underdog (undergoat?) story, all the characters on the team face both internal and external conflicts that prevent them from succeeding, until a scrappy young goat shows them the way to success.

Why Four-Quadrant Appeal Matters

For the longest time, animated movies were designed for kids. Rare was the movie rated above G; in fact, they were designed solely for kids to enjoy and parents to sleep through (I know my Dad slept through a lot of these when I was growing up).

Something changed in the 1990s. These films started appealing to older audiences. Movies like The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin subtly put in adult themes and jokes that parents appreciated and kids wouldn’t quite understand. In 1991, Beauty and the Beast became the first animated film to be nominated for Best Picture. Then Space Jam put live action basketball stars alongside Looney Tunes characters.

If the early 1990s Disney movies started breaking the mold, Toy Story shattered it. Animated movies were no longer about getting kids into the theater, but everyone in the four quadrants.

What’s a Four-Quadrant Film?

The movie industry breaks down basic demographics into four simple quadrants:

- Females Over 25

- Females Under 25

- Males Over 25

- Males Under 25

Most films tend to fall into just 1-2 boxes, such as Wuthering Heights for females over 25, or Sinners for both males and females over 25. Hitting a four-quadrant movie tends to make the most financial sense, as it appeals to all demographics. Recent examples of four-quadrant movies include Wicked, Freakier Friday, and Twisters.

GOAT touches on the four-quadrant concept as it appeals to all ages despite it being an animated film marketed mostly to kids. So, while it mostly sits in the two-quadrant area (male and female, under 25), there are aspects that appeal to the over 25 crowd.

“The film really has something for everybody, you know, the starter on the team, the sixth man, maybe the person who doesn’t get any minutes at all,” said Erick Peyton, a producer of GOAT, in a Blavity interview. “I think that that’s really what this sports film sort of represents. It’s really about bringing the family together, and hopefully everybody can be inspired through it.”

Can’t Go Wrong with Underdog and Sports

Being an underdog in a sports movie feels like a trope; perhaps that’s because it is. Long before Seabiscuit was a movie, the real underdog racehorse helped lift a broken nation in the Great Depression. It felt like if this old horse with a larger-than-normal jockey weighing it down can win, then maybe the audience can too.

It’s the fight and determination followed by the win, or at least some form of glory, that gives us hope. True stories of underdogs become great major motion pictures: Seabiscuit, Miracle, Next Goal Wins, and even Moneyball, to name a few.

GOAT is no exception. Granted it’s not a true story; but it is a sports/underdog story.

“Broadly, it’s Will’s journey as the underdog, the overlooked, the late bloomer, who has some doubts, but when he’s presented an opportunity, you can see the determination and the will to succeed, even if it’s not on your own timeline,” basketball MVP Stephen Curry said in an interview with Blavity. “I think that’s been part of my basketball journey from the time I started playing, and even now, it sometimes doesn’t sound right, but I still carry that underdog mentality with me… Hopefully there’s some relatability to Will, not just in basketball or sports, but something that anybody can see in terms of that moment of being ready for your opportunity, dreaming big and fighting for what you feel like you want in life.”

Managing Multiple Character Arcs on a Team

Sports films centered on teams present a unique screenwriting challenge. The writers must introduce a lot of memorable, unique characters and provide them with arcs. Team sports movies must also balance the protagonist’s journey, which should feel personal, with the team’s success, which feels collective.

GOAT demonstrates how to balance that equation by anchoring the story to Will the Goat, while giving each teammate a clear obstacle or flaw, such as Jett’s thinking she is the only one who can win, while also realizing the limitations of becoming an older athlete.

Ensemble movies require a lot of strong supporting characters, not just because they need to support the protagonist’s arc, but because they all must have their own stories that coincide with the central conflict. And, at the end of the sports movie, it’s not just about winning, it’s about characters succeeding as they overcome their individual and team conflicts.

Animation Can Go Big

Animation gives screenwriters far more freedom than the physical limitations of live action. Throughout GOAT, characters snap instantly into reaction beats, backgrounds shift colors for emphasis, and stunts defy physics and geography in ways that simply wouldn’t be possible in real life.

Sudden cartoony beats, like a smash cut to a visual gag, a character flattening against a wall, or a prop appearing at the perfect impossible moment, work because the world’s rules aren’t like reality. However, it’s important to establish what the world gets away with from the start. For instance, a visual beat for Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse will seem out of place in Shrek.

Whether a film is animated or live action, story is what ultimately endures. Animation simply expands the creative toolbox, allowing filmmakers to heighten emotion, bend reality, and translate real-life struggles into themes that resonate deeply with younger audiences. At their core, films like The Mighty Ducks and GOAT aren’t separated by medium, they’re united by a message: underdog athletes transformed by the belief of one person, whether a coach or a teammate. Formats may differ, but the power of an underdog story remains timeless.