When the film industry talks about genre screenplays or genre movies, it’s referring to stories built around specific storytelling frameworks that come with instant audience expectations.

- Horror promises scares and focuses on themes centered around fear.

- Science Fiction explores speculative future science concepts and worlds.

- Action delivers action and spectacle.

- Thrillers create suspense.

- Fantasy taps into myth and imagination.

These aren’t restrictive formulas screenwriters must follow - they’re narrative engines that help screenwriters and filmmakers quickly communicate tone, atmosphere, stakes, and the overall emotional experience. When used well, specific genre techniques become powerful storytelling tools that allow screenwriters to play with expectations, blend themes, and deliver stories that feel both familiar and fresh.

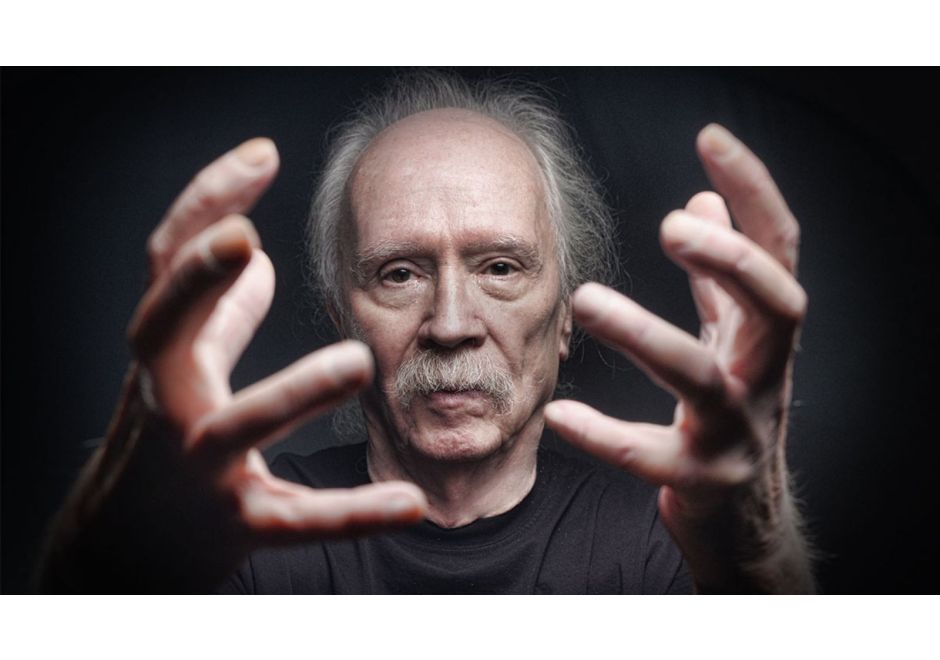

There’s no better classic genre storyteller than auteur John Carpenter. He has told more genre stories than most directors and cinematic storytellers.

Who Is John Carpenter?

John Carpenter attended the University of Southern California’s School of Cinema in the 1970s. His first breakout short film was Dark Star, a satirical science fiction that showcased a love for the genre, a minimalist approach, and a knack for subversive humor. He later expanded his short film into a low budget indie feature film in 1975, which would eventually become a cult classic.

In 1976, Carpenter directed Assault on Precinct 13, an intense siege thriller that reimagined the classic western Rio Bravo as a modern urban crime thriller. Two years later in 1978, the auteur made box office history with his iconic slasher horror flick Halloween. The film was made for roughly $300,000 and would go on to become the most profitable independent movie of its era while reshaping the horror landscape. An entire franchise was launched.

Over the decades that followed, Carpenter would go on to direct The Fog, Escape from New York, The Thing, Christine, Starman, Big Trouble in Little China, Prince of Darkness, They Live, Memoirs of an Invisible Man, and In the Mouth of Madness, among others, establishing himself as one of the most prolific and versatile genre filmmakers of all time, working across the genres of horror, science fiction, action, and fantasy. He became known for genre-blending long before the term took hold in screenwriting books, classes, and articles.

With that in mind, here we break down five of Carpenter’s best techniques he’s utilized in his genre movies.

1. What Scares You, Scares the Audience

Carpenter once said, “What scares me, scares you. We’re all afraid of the same things. That’s what makes horror such a powerful genre. All you have to do is ask what frightens you and you’ll know what frightens me.”

When you’re trying to determine what types of genre screenplays you want to write, the best place to start is by looking into the mirror and asking yourself what you want to see.

If you’re writing a horror movie, the best concepts are focusing on your own personal fears because, as Carpenter said, what scares you will scare others. We all have common fears. And when you focus on your own fears, you can delve even deeper into them for a greater impact on the audience who shares the same fears.

You can take this to deeper levels as well, outside of the horror genre.

- What potential future concepts intrigue you? (Science Fiction)

- What types of action sequences keep you on the edge of your seat? (Action Thrillers)

- What imaginative worlds or characters capture your imagination the most? (Fantasy)

With any of these genres (Horror, Science Fiction, Action, Thrillers, Fantasy), you can look at what interests and excites you the most, knowing that there are millions of others just like you. Then you can do your due diligence and explore which of those things have and haven’t been done yet. And if they’ve been done, you can explore the different ways and angles you can take those otherwise familiar tropes.

2. Put Characters in Situations of Confinement and Paranoia

If you watch John Carpenter movies, you’ll quickly see the common themes of confinement and paranoia throughout his entire filmography. These themes create two of the most important elements of genre screenplays - conflict and high stakes.

- Assault on Precinct 13 was set in a police station where characters were locked within and under constant and growing siege.

- Halloween took place in the small town of Haddonfield, specifically within the confines of a suburban neighborhood as a babysitter, her friends, and her neighbors were being stalked and murdered by a horrifying shape (which he was referred to as in the script) in the shadows.

- The Fog takes place in a small coastal community besieged by an ominous fog with faceless terrors within.

- Escape from New York is set within a future-version of New York City that was cut off from the rest of the world as a prison, with the protagonist tasked with finding the President of the United States, who had crash-landed in the city with important information in his possession.

- The Thing has the characters cut off from civilization while manning an Antarctic research facility threatened by a shapeshifting alien that could take on the form of any one of them.

- Big Trouble in Little China has the characters going into the depths of Chinatown, working together to save a kidnapped young woman.

- Prince of Darkness sequesters a group of scientific grad student researchers, their professor, and a priest within an old church as the prince of darkness is about to be released onto the world.

- They Live takes place in the homeless community backstreets of a city amidst the revelation that the world they see around them is a false facade created by an alien race.

- In the Mouth of Madness traps the protagonist in a fictional town of horrors he can’t escape as he struggles to find a missing best-selling horror novelist.

When characters are confined within a space and dealing with the paranoia of not knowing who and what they can trust, the audience will go on that ride with those characters. Conflict is extremely enhanced, and the stakes of the story are heightened.

3. Throwing Characters Into the Fire From Page One

John Carpenter doesn’t ease characters into danger. He doesn’t spend the first act introducing characters and slowly building to an eventual turn of events. Instead, he throws his characters into the fire of the conflict as quickly as possible.

In short, he gets to the point right away, wasting little to no time engaging the audience.

- In Halloween, Carpenter throws the audience in the fire right away by showing little Michael Myers murdering his sister. Then we jump to his escape from a sanitarium years later. After that, he’s back in Haddonfield, stalking teenage babysitter Laurie.

- In Escape from New York, a shackled convict, Snake Plissken, is brought in to take on the mission of saving the President of the United States. Within the opening few minutes, he takes on the mission, is injected with an explosive device to keep him from running, dropped into the prison city, and facing constant threats as he searches for the President.

- In The Thing, a sled dog is being chased and shot at by a helicopter until it runs into the research base where the characters within are instantly thrust into the conflict as a shooter who can’t speak English begins shooting at them (at the dog, unbeknownst to them at first). He’s taken out and the sled dog/alien shapeshifter begins to take over the base.

- In Big Trouble in Little China, Jack Burton offers a ride to a friend, leading to his friend’s girlfriend being kidnapped, and their pursuit of her kidnappers leading them into the depths of Chinatown, and a strange underworld of fantasy and Kung Fu.

- In Prince of Darkness, the group of grad students are talked into attending a research study over the weekend, which soon-after leaves them locked in an old church with evil lurking.

- In They Live, protagonist Nada, a homeless drifter, discovers something nefarious going down in the backstreets of the city, leading him to try on a pair of glasses that allow him to see the true (and horrific) world around him.

- In In the Mouth of Madness, an insurance claims investigator is quickly attacked by an awe-wielding fan of the best-selling horror author he’s been tasked with finding, leading him to the fictional town of horrors he can’t escape.

All of these things happen within the opening few minutes of each movie.

As a screenwriter, you’re always looking to capture the attention of the script reader and audience as quickly as possible. You want them immediately engaged and compelled to read or watch on. Throwing your characters into the fire of the conflict as quickly as possible allows you to do that. Then you can slowly introduce the characters and their arcs by way of their actions and reactions to the conflict at hand.

Sure, the Hero’s Journey often teaches us to introduce characters in their ordinary world first so we have a context to separate them from how they were to the characters they become amidst the conflict. However, you can accomplish that within just a page or two (or even less).

4. Make Your Protagonists Pragmatic and Flawed

Characters within John Carpenter movies don’t win because they’re perfect, idealistic, or even outright heroic. They win because they are pragmatic, which is to say that they adapt quickly, act practically, and hold efficient and realistic solutions high over emotions and ideology.

In Carpenter’s genre movies - as well as most successful genre movies - heroism is about response, not idealism. Genre audiences love characters who adapt quickly, make hard choices, and accept the rules of the nightmare they’ve been thrust into. Audiences are able to then identify with the characters more. Why? Because they’re more realistic and relatable.

Some of Carpenter’s films may have seemingly “perfect” protagonists like Laurie in Halloween, but Laurie was completely unsuited for the threat at hand. She relied on quick adaptation, practical solutions, and overall survival instincts.

But other Carpenter films also have flawed protagonists like Napoleon Winston in Assault on Precinct 13, Snake Plissken in Escape from New York, Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China, MacReady in They Live, and Nada in They Live. When these flawed characters react in pragmatic and realistic ways, the audience can more easily connect with them.

5. Blend Genres to Expand the Audience and Make Concepts More Intriguing

One of Carpenter’s most underappreciated strengths is his mastery of genre blending.

Genre blending isn’t about mashing concepts together randomly. It’s about using one genre to enhance the other, and vice versa.

Carpenter has done this throughout his whole career.

- Assault on Precinct 13 is an urban crime thriller built on the thematic and structural bones of a classic western.

- The Fog merges the traditional ghost-horror story with pirate folklore.

- Escape from New York blends dystopian science fiction with action and western (Plissken is like a gunslinger from the Old West) mythology.

- The Thing is classic monster horror fused with science fiction.

- Big Trouble in Little China blends action, horror, fantasy, martial arts, and comedy together.

- Prince of Darkness blends an evil horror thriller concept with scientific undertones, complete with time travelling messages from the future.

- They Live mixes science fiction with social satire.

- In the Mouth of Madness blends Lovecraftian cosmic horror with psychological thriller and metafiction subgenres.

Blending genres broadens the audience appeal, creates fresh and new story concepts, and subverts tired genre expectations.

Learning from John Carpenter’s 50 Years in Cinematic Genre Storytelling

If you’re looking to learn about genre screenwriting and genre blending, look no further than John Carpenter’s filmography over the last fifty years.

From his early indie cult flick Dark Star, to his most notable and celebrated movies from 1976’s Assault on Precinct 13 through 1994’s In the Mouth of Madness - and even to his further genre films like 1995’s Village of the Damned, 1996’s Escape from L.A., 1998’s Vampires, and 2001’s Ghosts of Mars, and 2010’s The Ward - Carpenter gave screenwriters and filmmakers timeless blueprints on how to successfully create cinematic genre stories.

He was a genre storyteller ahead of his time.