Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was only 18 years old when she began writing what would become one of the most famous sci fi horror novels of all time, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Published in 1818, the story of a disturbed scientist determined to create life by constructing and reanimating a humanoid creature became a benchmark of Gothic horror fiction, inspiring generations of filmmakers to reimagine its dark themes of creation and consequence.

In just the last few years, the novel’s iconography has been echoed in cinematic works as wide ranging as Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things (2023), James Gunn’s animated DC series Creature Commandos (2024), and Guillermo Del Toro’s long-gestating passion project, the new Netflix adaptation, Frankenstein (2025).

Here are some of the most memorable and groundbreaking Frankenstein films that have electrified audiences over the past century.

FRANKENSTEIN (1931)

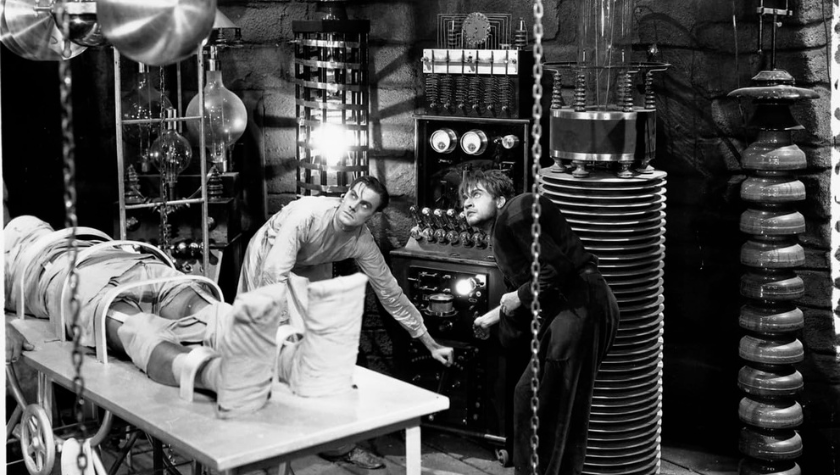

Frankenstein movies are nearly as old as cinema itself, with an early silent adaptation appearing in 1910 from Thomas Edison’s motion picture company. But it wasn’t until the advent of sound that the definitive film version came to life during a boom of horror films from Universal Studios. In the early 1930s, when the studio was struggling financially, the smash success of their first horror talkie, the Bela Lugosi-starring Dracula (1931), caused producer Carl Laemmle Jr. to fasttrack further horror adaptations. The first and most obvious choice was Frankenstein (1931).

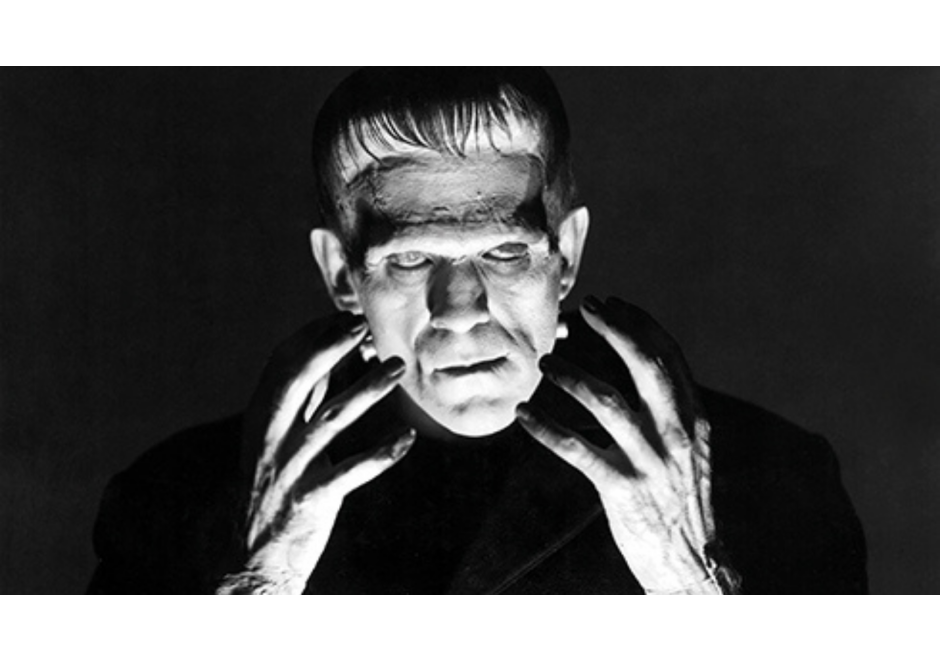

James Whale, a successful British stage director, signed on to make the film, and was sitting in the studio commissary one day when he noticed an actor with a very distinct bone structure who he thought might be right for The Monster. That man was British actor Boris Karloff, and in collaboration with make-up genius Jack Pierce, they managed to create the design of Frankenstein’s Monster that everyone recognizes today.

The film became a box office hit, spawning several sequels and turning Karloff into a star. Though the scares and German Expressionist-influenced design thrilled audiences, it’s the very apparent humanism that stands out almost a century later. Whale was an openly gay man in a society that expressly forbid his sexual identity, Karloff tried to hide his Indian heritage to blend into British society as a young man, and Clive suffered from debilitating alcoholism which would lead to his death, knowing all too well what it meant not to battle one’s demons. These personal experiences of grappling with identity, societal prejudice, and guilt, come through on the screen, and helped make Frankenstein so much more than just a scary movie.

ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948)

Frankenstein’s Monster appeared in six other Universal horror films at the same time as the studio’s string of comedy hits starring comic duo Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. But as the 1940s were coming to a close, none of the studio’s dependable ingredients were achieving as much box office success as they once had. They determined that perhaps it was time to put the two comedians up against their stable of famed movie monsters in one movie, the sort of crossover event that the Marvel Cinematic Universe would utilize to great success in the 2010s. So it was decided that Dracula, The Wolf Man, and Frankenstein’s Monster, as played by Glenn Strange, would join the comic duo for Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

Abbott and Costello play railway station baggage clerks who have the misfortune of receiving two large crates within which lie Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster. By the film’s end, the duo is trapped in a gothic castle being chased by the Universal Monsters. The plot may be farcical, but the scares are played totally straight, catnip for the two comedians to react to, and though the titular creature has less screentime than the others, there are few moments in the film more potent than The Monster throwing an operating room nurse through a window. The film’s success led to several other collaborations between the comics and the monsters, and became a prime influence on countless filmmakers, not least of all Quentin Tarantino, who credits seeing this film at a young age with helping him develop his genre mash-up style.

THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1957)

By the mid 1950s, the Universal Monster output had all but fizzled out, save a few Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954) movies. The popular horror films of the day were b-movies about aliens and giant monsters that reflected the paranoia of the Cold War and atomic age. But Frankenstein’s monster and the Gothic world he inhabited would soon find resurrection across the pond in England. Hammer Film Productions specialized in quota-quickies, films made cheaply and locally to be programmed in support of more substantial movies. After having some success in the horror and sci-fi genres, they decided to take a shot at adapting Frankenstein. Without any lofty expectations for success, Hammer put together a classy, efficient adaptation called The Curse Of Frankenstein (1957), the first version to be shot in color.

Future Star Wars (1977) villain Peter Cushing played Victor Frankenstein, less as the reluctant, tortured scientist, and more as a cruel tyrant. The role of The Creature went to Christopher Lee, who modern audiences will know from the Star Wars prequels and as Saruman in the Lord Of The Rings films. The Creature’s make-up emphasized the deformity and patchwork nature of being constructed of different peoples’ bodies, and given the use of color to capture the gory goings-on, the film terrified audiences. Against all expectations, it became an extraordinary, world-wide hit, and led Hammer to create a Dracula film series, starring Lee as the vampire count and Cushing as Van Helsing, and countless Frankenstein sequels that lasted well into the 1970s. Hammer’s low budget gamble proved that the public still had a strong desire to see Frankenstein onscreen.

FRANKENSTEIN VS. BARAGON (1965)

In 1965, Ishirō Honda, who directed Godzilla (1954) and many of its kaiju sequels featuring giant, battling monsters, signed on to direct Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965). In a plot that makes Abbott and Costello seem absolutely grounded, a Frankenstein monster begins growing in size after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Though he’s chastised by scientists and society alike, when a monster known as Baragon starts terrorizing the city, Frankenstein swoops in to defend the people from the real monster. While the premise may seem absurd, the Japanese kaiju movies are not all that different in theme from Shelley’s original text. Godzilla was a direct response to the atomic bombings of Japan and their traumatic fallout, a man-made scientific nightmare in the realm of Shelley’s themes. It’s all too natural then, that Frankenstein’s monster would emerge among the atomic monsters of Japanese cinema.

And he would return in Honda’s 1966 cult classic, The War of the Gargantuans, solidifying Shelley’s legacy in the Japanese kaiju world. And her legacy wasn’t showing any signs of fading. The 1970s would see the character expand across even more genres, including in one of the most famous and well-loved comedies of all time.

YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974)

Comic writer/director Mel Brooks and one-of-a-kind actor Gene Wilder were in the middle of production on their comedy-western, Blazing Saddles, when Wilder pitched Brooks an idea for a comic take on the Universal Frankenstein films called Young Frankenstein (1974). Brooks was reluctant given all of the recent permutations of Frankenstein. In addition to the ongoing Hammer series, Andy Warhol’s team had just produced an erotic take on the material with Flesh For Frankenstein (1973). A blaxploitation version called Blackenstein (1973) had just been released. There was even a new General Mills cereal called Franken Berry on grocery store shelves. But by the time Brooks and Wilder were done with the script, it had turned out so well that Brooks agreed to direct.

The film was a smash, ranking alongside Blazing Saddles as one of the highest grossing of the year, and eventually even received a Broadway musical treatment. But the success of Young Frankenstein isn’t just due to the laughs, it’s also due to the seriousness Brooks and Wilder give to the themes and emotions of the core text beneath the vaudevillian gags. While over the next two decades the Monster remained a mainstay in various b-movies and cartoons alike, the next major studio adaptation to bear the Frankenstein name would forgo any attempt at laughs or exploitation, adhering instead to a deadly serious treatment of the novel itself.

MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN (1994)

By the end of the 1970s, Gothic horror had gone out of fashion and the Hammer monster movies were forced to end their run. But even in the more popular gory teen slashers and action movies of the 1980s, there were echoes of Shelley, from Tobe Hooper’s The Funhouse (1981) to Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator (1985) and even the action hit, Robocop (1987). It wasn’t until the 1990s that Francis Ford Coppola pumped life back into gothic horror with his version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), and decided to produce another faithful, prestige adaptation of a classic horror text, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994).

Kenneth Branagh, famous for his acclaimed Shakespeare adaptations, directed and played the role of Victor Frankenstein, and former Coppola collaborator, Robert De Niro, took the role of The Creature.

The film grossed over $100m at the box office, and was one of several 90s films to use huge movie stars in classic horror stories. Jack Nicholson played a Wolf Man type character in Wolf (1994), Julia Roberts played the wife of Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde in Mary Reilly (1996), and Kevin Bacon played an iteration of The Invisible Man (1933) in Hollow Man (2000). Universal even dusted off its Monster canon with a much-beloved reboot franchise of The Mummy (1999), and director Stephen Sommers followed it up with Van Helsing (2003), in which Hugh Jackman’s comic book version of the titular vampire fighter goes up against Frankenstein’s Monster, among others. But the horror genre was once again moving away from the gothic into slasher remakes and low budget shockers like Saw (2004), and Frankenstein’s next significant appearances would come in a bizarre variety of 2010s studio films.

FRANKENWEENIE (2012)

If there’s one person who almost assuredly watched all of the aforementioned works during his childhood, it’s Tim Burton. “I grew up watching the Universal horror movies, Japanese monster movies and pretty much any kind of monster movie,” he told the Hollywood Reporter, “It was strange. Just because you like monster movies, people thought you were weird.”

Growing up in the suburbs of Burbank, Burton’s outsider status made him empathize in particular with Frankenstein’s monster. It’s no surprise then that while working for Disney’s animation department, 26-year-old Burton made a short film that transposed the Frankenstein story to the suburbs, with a boy reanimating his dead dog. The black and white Universal Horror homage, Frankenweenie (1984) got Burton fired from Disney, but it also helped him break into a feature directing career. He would revisit the same suburban Frankenstein mythos with one of his most beloved films, Edward Scissorhands (1990), about a humanoid invented by a scientist.

After the success of Alice In Wonderland (2010), Disney allowed Burton to remake that first breakout short as a black and white stop motion feature. Frankenweenie (2012) is among the most enjoyable children’s versions of the Frankenstein story, and a culmination of Burton’s many Shelley-inspired outsider stories and horror influences. It was a box office hit and garnered an Academy Award nomination for Best Animated Feature among many other accolades, an acknowledgment of Burton’s career-spanning love of misfits and gothic horror.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO’S FRANKENSTEIN (2025)

Mexican filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro always felt like an outsider who didn’t belong in the world he was born into. So when he went to the cinema to see the 1931 Frankenstein, he immediately recognized himself in Karloff’s Monster, describing that first viewing as a religious experience.

It makes sense then that his filmography is full of chastised outsiders like Hellboy (2004), the Amphibian Man from his Oscar-winning The Shape Of Water (2017), or most recently, Pinocchio (2022), and that the most monstrous characters usually come in the form of bureaucratic men. After Pinocchio won the Best Animated Film Oscar for Netflix, the studio granted Del Toro his greatest life-long desire, to make his very own version of the Mary Shelley story.

Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025), which premiered at the Venice Film Festival to an ecstatic standing ovation, is a culmination of sorts, a grand operatic treatment of Shelley’s text with Oscar Isaac playing the tortured Victor, and Jacob Elordi taking on The Creature. The mammoth production utilized vast, real life locations across the UK in addition to gigantic sets with meticulously detailed production design typical of Del Toro’s works, to create the largest cinematic world of any Frankenstein adaptation to date. But at its core is what Del Toro describes as a family drama about fathers and sons. Nearly a century after Karloff’s Monster stepped out of the shadows, Del Toro finally gets to contribute his verse to the cinematic legacy of Shelley’s novel, in theaters on October 17 and on Netflix November 7.

And Del Toro’s is far from the last word on Frankenstein. Next year Christian Bale will play the Creature alongside Jessie Buckley in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Bride! (2026) and more adaptations, literal or otherwise, are inevitable. The battle for humanism amidst scientific innovation is an eternal one, and prejudices against those considered different from imposed societal norms are unfortunately as prevalent as ever, so stories echoing the themes of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein are not only still relevant, they’re an absolute necessity.